Underestimation of pregnancy risk among women in Viet Nam

Background: Addressing women’s inaccurate perceptions of their risk of pregnancy is crucial to improve

contraceptive uptake and adherence. Few studies, though, have evaluated the factors associated with

underestimation of pregnancy risk among women at risk of unintended pregnancy.

Methods: We assessed the association between demographic and behavioral characteristics and underestimating

pregnancy risk among reproductive-age, sexually-active women in Hanoi, Vietnam who did not desire pregnancy

and yet were not using highly-effective contraception (N = 237). We dichotomized women into those who

underestimated pregnancy likelihood (i.e., ‘very unlikely’ they would become pregnant in the next year), and those

who did not underestimate pregnancy likelihood (i.e., ‘somewhat unlikely,’ ‘somewhat likely’ or ‘very likely’). We used

bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models to identify correlates of underestimating pregnancy risk.

Results: Overall, 67.9% (n = 166) of women underestimated their pregnancy risk. In bivariable analysis,

underestimation of pregnancy risk was greater among women who were older (> 30 years), who lived in a town or

rural area, and who reported that it was “very important” or “important” to them to not become pregnant in the

next year. In multivariable analysis, importance of avoiding pregnancy was the sole factor that remained statistically

significantly associated with underestimating pregnancy risk (odds ratio [OR]: 0.11; 95% confidence interval [CI],

0.05–0.25). In contrast, pregnancy risk underestimation did appear to vary by marital status, ethnicity, education or

other behaviors and beliefs relating to contraceptive use.

Conclusions: Findings reinforce the need to address inaccurate perceptions of pregnancy risk among women at

risk of experiencing an unintended pregnancy

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Underestimation of pregnancy risk among women in Viet Nam

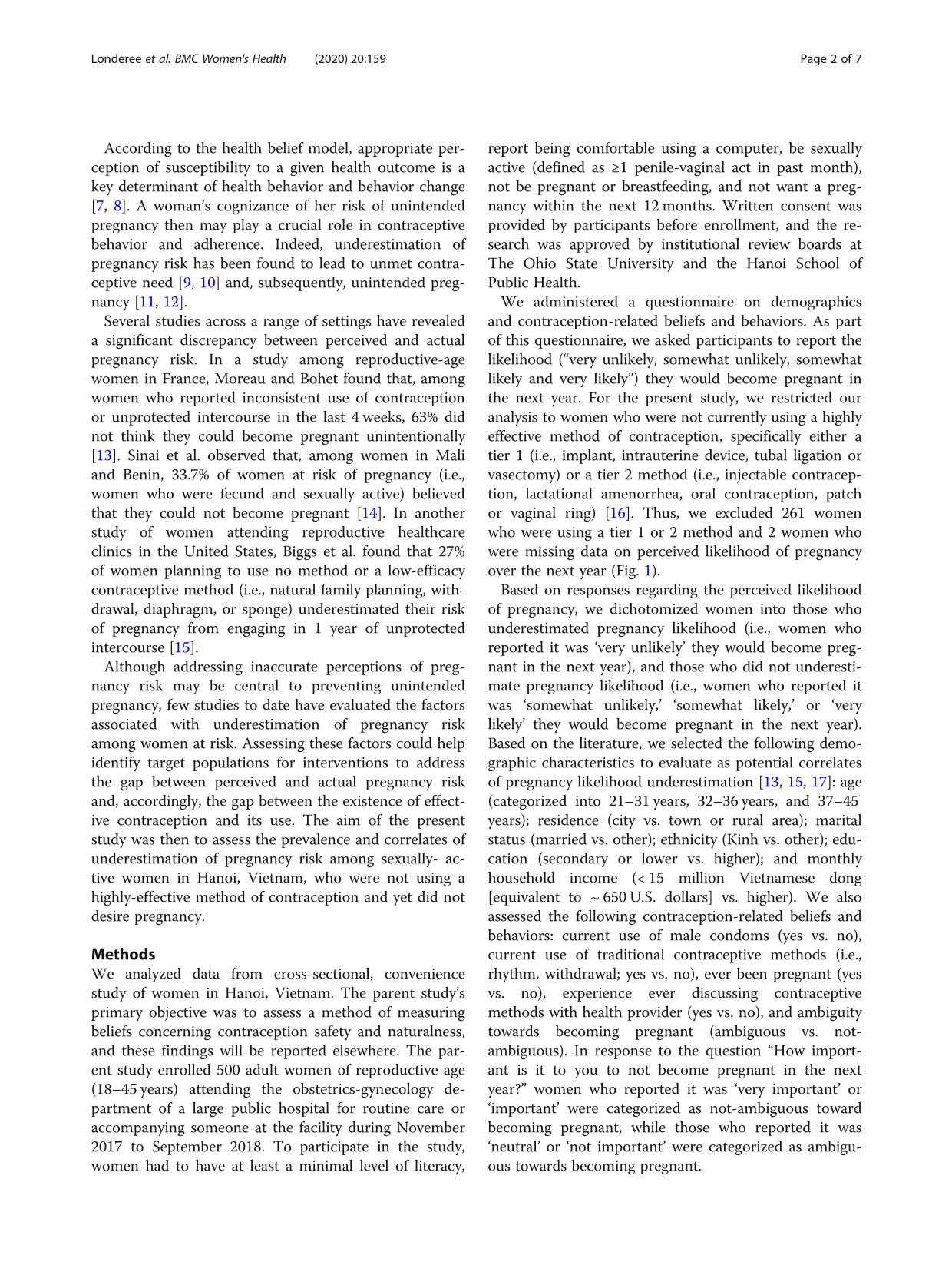

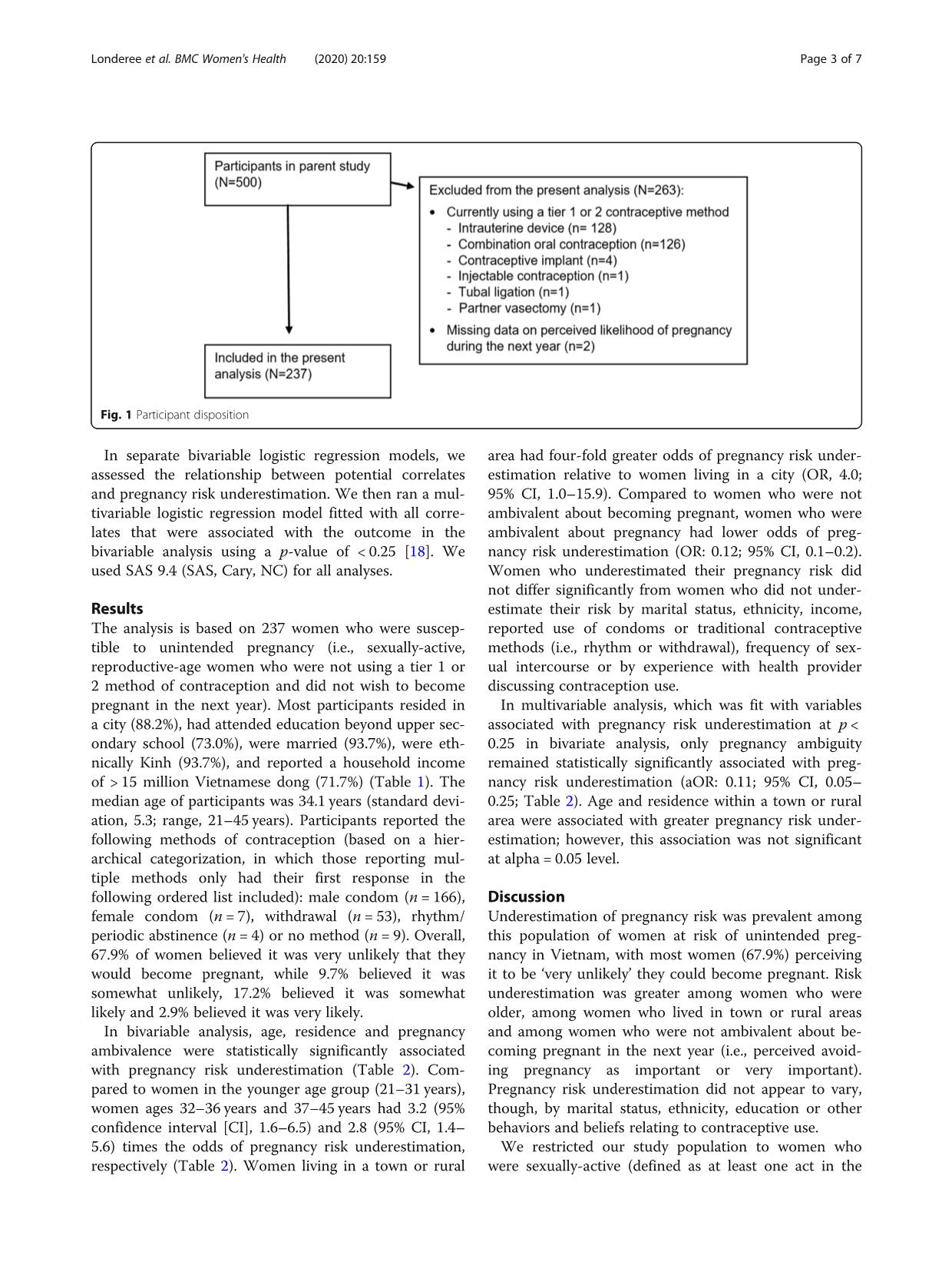

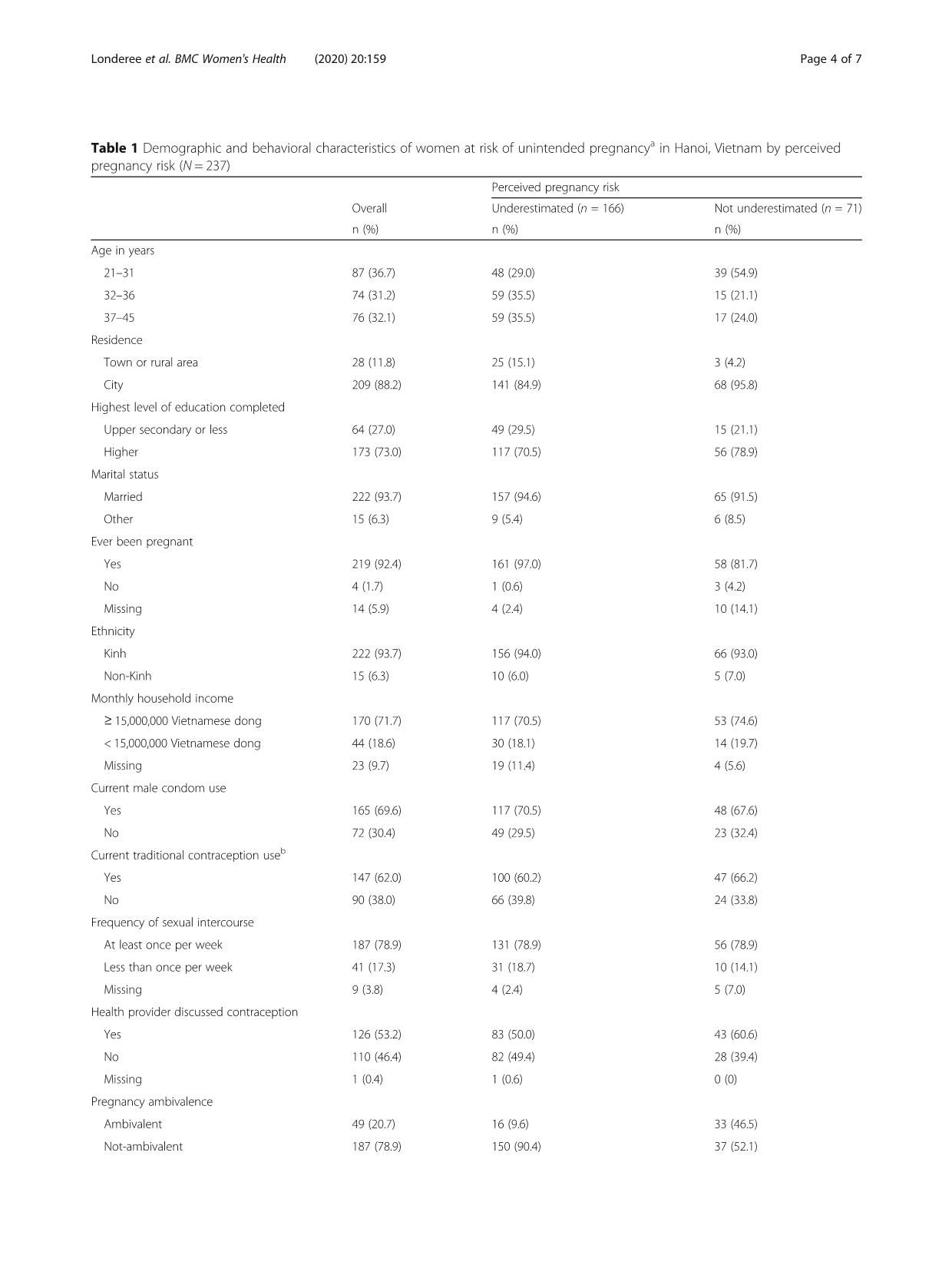

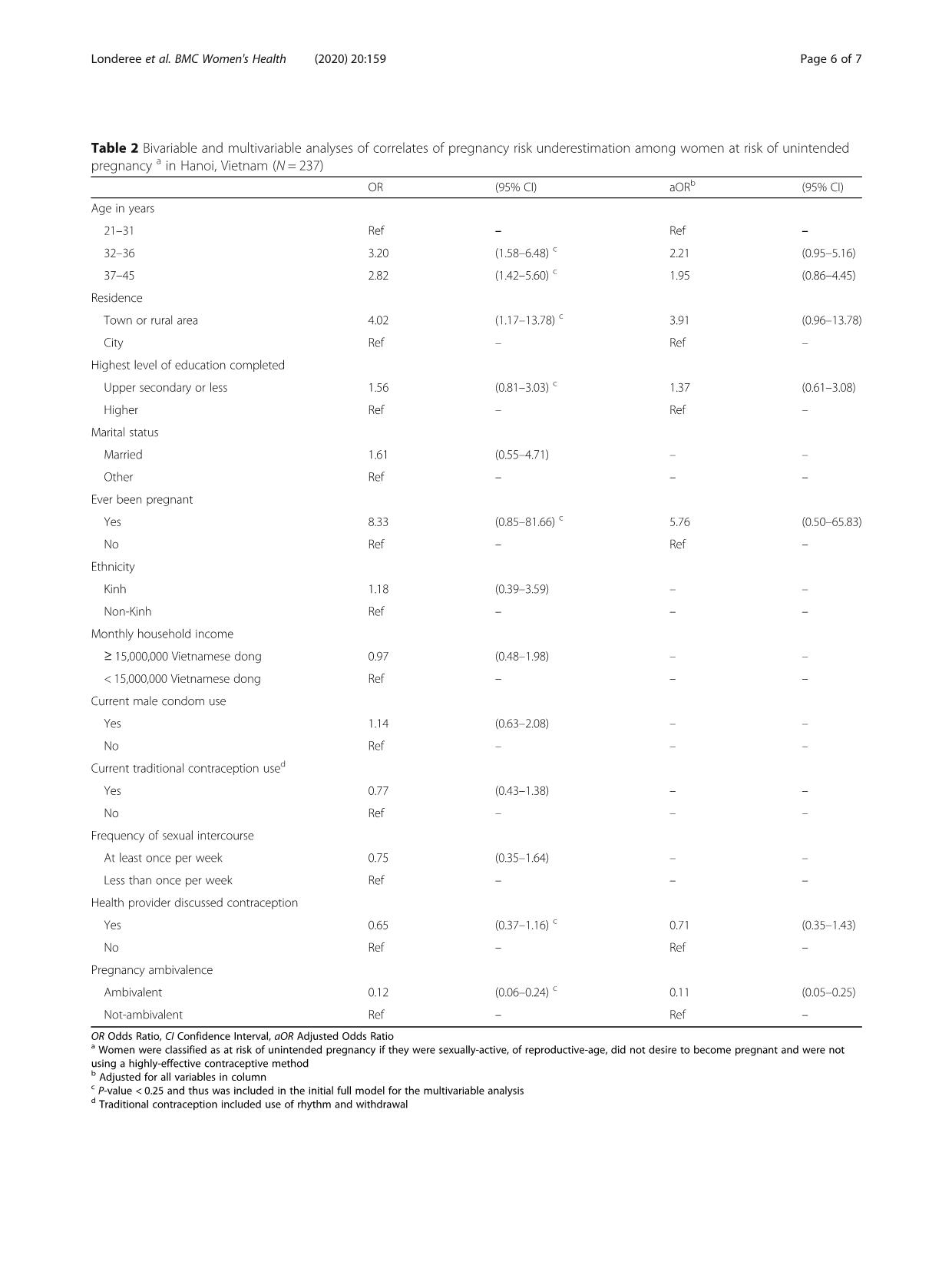

RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Underestimation of pregnancy risk among women in Vietnam g s o , of p birth outcomes [2], increased levels of pregnancy-related tended pregnancies occur [1, 4], and where the health n who desire Londeree et al. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:159 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01013-6appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commonsto prevent pregnancy is critical. © The Author(s). 2020 Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give Health, Cunz Hall, 1841 Neil Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA Full list of author information is available at the end of the articlebarriers to contraception use among wome* Correspondence: gallo.86@osu.edu1Division of Epidemiology, The Ohio State University, College of Publicmorbidity and mortality [3, 4], as well as mental health infrastructure is often ill-equipped to handle the conse- quences of unintended pregnancy, understanding theilies. Consequences of these pregnancies include poorand yet were not using highly-effective contraception (N = 237). We dichotomized women into those who underestimated pregnancy likelihood (i.e., ‘very unlikely’ they would become pregnant in the next year), and those who did not underestimate pregnancy likelihood (i.e., ‘somewhat unlikely,’ ‘somewhat likely’ or ‘very likely’). We used bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models to identify correlates of underestimating pregnancy risk. Results: Overall, 67.9% (n = 166) of women underestimated their pregnancy risk. In bivariable analysis, underestimation of pregnancy risk was greater among women who were older (> 30 years), who lived in a town or rural area, and who reported that it was “very important” or “important” to them to not become pregnant in the next year. In multivariable analysis, importance of avoiding pregnancy was the sole factor that remained statistically significantly associated with underestimating pregnancy risk (odds ratio [OR]: 0.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.05–0.25). In contrast, pregnancy risk underestimation did appear to vary by marital status, ethnicity, education or other behaviors and beliefs relating to contraceptive use. Conclusions: Findings reinforce the need to address inaccurate perceptions of pregnancy risk among women at risk of experiencing an unintended pregnancy. Keywords: Contraception, Health knowledge, attitudes, practice, Pregnancy, unplanned, Risk assessment, Vietnam Background Of pregnancies occurring worldwide from 2000 to 2014, an estimated 44% of were unintended [1]. Unintended pregnancies, defined as pregnancies that are unwanted or mistimed at the time of conception, pose a substantial social and economic burden for women and their fam- concerns and lost educational opportunities among chil- dren [5, 6]. Despite these consequences, a large gap re- mains between the availability of contraceptive methods and their use. An estimated 80% of the 85 million women annually who have an unintended pregnancy are not using contraception at the time of conception [4]. In lower and middle-income countries, where most unin-pregnancy risk among reproductive-age, sexually-active women in Hanoi, Vietnam who did not desire pregnancyJessica Londeree1, Nghia Nguyen2, Linh H. Nguyen2, Dun Abstract Background: Addressing women’s inaccurate perception contraceptive uptake and adherence. Few studies, though underestimation of pregnancy risk among women at risk Methods: We assessed the association between demogralicence and your intended use is not permitte permission directly from the copyright holder The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedica data made available in this article, unless otheH. Tran3 and Maria F. Gallo1* f their risk of pregnancy is crucial to improve have evaluated the factors associated with unintended pregnancy. hic and behavioral characteristics and underestimatingd by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain . To view a copy of this licence, visit tion waiver ( applies to the rwise stated in a credit line to the data. Londeree et al. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:159 Page 2 of 7According to the health belief model, appropriate per- ception of susceptibility to a given health outcome is a key determinant of health behavior and behavior change [7, 8]. A woman’s cognizance of her risk of unintended pregnancy then may play a crucial role in contraceptive behavior and adherence. Indeed, underestimation of pregnancy ... 7) 156 (94.0) 66 (93.0) Non-Kinh 15 (6.3) 10 (6.0) 5 (7.0) Monthly household income ≥ 15,000,000 Vietnamese dong 170 (71.7) 117 (70.5) 53 (74.6) < 15,000,000 Vietnamese dong 44 (18.6) 30 (18.1) 14 (19.7) Missing 23 (9.7) 19 (11.4) 4 (5.6) Current male condom use Yes 165 (69.6) 117 (70.5) 48 (67.6) No 72 (30.4) 49 (29.5) 23 (32.4) Current traditional contraception useb Yes 147 (62.0) 100 (60.2) 47 (66.2) No 90 (38.0) 66 (39.8) 24 (33.8) Frequency of sexual intercourse At least once per week 187 (78.9) 131 (78.9) 56 (78.9) Less than once per week 41 (17.3) 31 (18.7) 10 (14.1) Missing 9 (3.8) 4 (2.4) 5 (7.0) Health provider discussed contraception Yes 126 (53.2) 83 (50.0) 43 (60.6) No 110 (46.4) 82 (49.4) 28 (39.4) Missing 1 (0.4) 1 (0.6) 0 (0) Pregnancy ambivalence Ambivalent 49 (20.7) 16 (9.6) 33 (46.5) Not-ambivalent 187 (78.9) 150 (90.4) 37 (52.1) Londeree et al. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:159 Page 4 of 7 t r -ac Londeree et al. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:159 Page 5 of 7past month) and not currently using highly-effective contraception. Women having less frequent sex (includ- ing those who experience forced sex) or those using a highly-effective contraceptive method can face the risk unintended pregnancy. However, we focused our study on assessing correlates of reported unintended preg- nancy risk among women who are most susceptible to unintended pregnancy, and thus should be the target of public health interventions. As perceived susceptibility to a health outcome is a key determinant of behavior change, the high prevalence of pregnancy risk underesti- mation in our sample reinforces the need for interven- tions to address inaccurate perceptions of pregnancy risk, especially among women who are older and who live in non-urban settings. Future studies should assess the effect of interventions shown to improve reproduct- ive and contraceptive knowledge, such as entertainment education (e.g., radio drama) [19], tailored oral education [20], or other health promotion materials (e.g., posters, brochures) [21, 22], on correcting inaccurate perceptions of pregnancy risk in this setting. Our study also reinforces the need for a more nuanced categorization of contraceptive need. At present, contra- ceptive use is commonly categorized into ‘met’ and ‘un- met’ need, based on fecundity, sexual activity and current contraceptive use. Incorporating perception of contraceptive need into the categorization of contracep- tive use could further elucidate why some women fail to use effective contraceptive methods, despite their avail- ability. One such strategy of categorization, known as the Tékponon Jikuagou approach, splits contraceptive use into five categories: real met need (current users of a Table 1 Demographic and behavioral characteristics of women a pregnancy risk (N = 237) (Continued) Overall n (%) Missing 1 (0.4) aWomen were classified as at risk of unintended pregnancy if they were sexually using a highly-effective contraceptive method bTraditional contraception included use of rhythm and withdrawalmodern method), perceived met need (current users of a traditional method), real no need, perceived no need (those with a physiological need for family planning who perceive no need), and perceived unmet need (those who realize they have a need but do not use a method) [14]. The use of this categorization could better inform targeted behavioral interventions to prevent unintended pregnancy. We note that our results should not be generalized to users of highly-effective contraception as such general- izations could be subject to selection bias. Our findings concerning pregnancy ambivalence illustrate thispotential source of bias; the women in our sample who were not ambiguous about avoiding pregnancy were more likely to underestimate the probability they would become pregnant. Initially, this finding may seem un- usual as one may expect that those who are most adam- ant about avoiding pregnancy would be more aware of their pregnancy risk. However, we may also expect that most women who choose not to use contraceptives, des- pite having great desire to avoid pregnancy, would be- lieve it is improbable they could naturally conceive. In short, by selecting on non-use of highly-effective contra- ception, we observe an association between pregnancy ambiguity and risk underestimation that may otherwise not be observed in a sample of all women of reproduct- ive age. Indeed, in a study of contraceptive users and non-users in the United States, Rahman et al. found that women who were ambivalent about pregnancy were more likely to have accurate perceptions of their risk of pregnancy [17], in contrast to our own findings. Regarding the association between pregnancy risk underestimation and age, we acknowledge that the abil- ity to become pregnant naturally declines with increas- ing age. Women’s fecundity begins to gradually lessen at age 32, before dropping rapidly at the age of 37 with the onset of perimenopausal menstrual irregularity [23]. Thus, though all women in this sample were of repro- ductive age, the low perceived pregnancy likelihood among older women could be based – in part – on bio- logic reality. Nonetheless, if reproductive age women are sexually active and not using highly-effective contracep- tion, the risk of unintended pregnancy persists. There- fore, the belief that pregnancy is very unlikely remains isk of unintended pregnancya in Hanoi, Vietnam by perceived Perceived pregnancy risk Underestimated (n = 166) Not underestimated (n = 71) n (%) n (%) 0 (0) 1 (1.4) tive, of reproductive-age, did not desire to become pregnant and were notan underestimation of pregnancy likelihood, especially for women under the age of 37 years. Additionally, we observed that the level of pregnancy risk underestima- tion was similar in older age groups: women ages 32–37 years had nearly identical odds of pregnancy risk under- estimation relative to women ages 38–45 years. These findings further suggest that women’s perception of their ability to become pregnant does not fully align with the natural decline in fecundity with age. Our study population was relatively homogenous; most participants in our sample were married, of the Kinh ethnicity and resided in an urban setting. This Table 2 Bivariable and multivariable analyses of correlates of pregnancy risk underestimation among women at risk of unintended pregnancy a in Hanoi, Vietnam (N = 237) OR (95% CI) aORb (95% CI) Age in years 21–31 Ref – Ref – 32–36 3.20 (1.58–6.48) c 2.21 (0.95–5.16) 37–45 2.82 (1.42–5.60) c 1.95 (0.86–4.45) Residence Town or rural area 4.02 (1.17–13.78) c 3.91 (0.96–13.78) City Ref – Ref – Highest level of education completed Upper secondary or less 1.56 (0.81–3.03) c 1.37 (0.61–3.08) Higher Ref – Ref – Marital status Married 1.61 (0.55–4.71) – – Other Ref – – – Ever been pregnant Yes 8.33 (0.85–81.66) c 5.76 (0.50–65.83) No Ref – Ref – Ethnicity Kinh 1.18 (0.39–3.59) – – Non-Kinh Ref – – – Monthly household income ≥ 15,000,000 Vietnamese dong 0.97 (0.48–1.98) – – < 15,000,000 Vietnamese dong Ref – – – Current male condom use Yes 1.14 (0.63–2.08) – – No Ref – – – Current traditional contraception used Yes 0.77 (0.43–1.38) – – No Ref – – – Frequency of sexual intercourse At least once per week 0.75 (0.35–1.64) – – Less than once per week Ref – – – Health provider discussed contraception Yes 0.65 (0.37–1.16) c 0.71 (0.35–1.43) No Ref – Ref – Pregnancy ambivalence Ambivalent 0.12 (0.06–0.24) c 0.11 (0.05–0.25) Not-ambivalent Ref – Ref – OR Odds Ratio, CI Confidence Interval, aOR Adjusted Odds Ratio a Women were classified as at risk of unintended pregnancy if they were sexually-active, of reproductive-age, did not desire to become pregnant and were not using a highly-effective contraceptive method b Adjusted for all variables in column c P-value < 0.25 and thus was included in the initial full model for the multivariable analysis d Traditional contraception included use of rhythm and withdrawal Londeree et al. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:159 Page 6 of 7 Londeree et al. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:159 Page 7 of 7homogeneity limits the generalizeability of our findings to similar population groups. Additionally, our conveni- ence sampling strategy furthers limits the generalizability of our findings, as women seeking care from a single fa- cility in Hanoi may not be representative of all reproductive-age women in the region. Despite these limitations, our study is the first to quantitatively assess correlates of inaccurate pregnancy risk estimation in a non-Western context. Conclusions As women in middle and low-income countries experi- ence disproportionate rates of unintended pregnancy [1], it is crucial to assess potential modifiable factors contrib- uting to poor contraceptive use in these regions. In the present study of women at risk of unintended pregnancy in Hanoi, Vietnam, most women underestimated their risk of pregnancy. These findings highlight the need for interventions to address women’s misconceptions of their pregnancy risk. Abbreviations aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio Acknowledgements Not applicable. Authors’ contributions NN and MG developed the study protocol. LHN and DHT led the data collection. JL conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. Funding This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [OPP1171894] and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [UL1TR001070]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or the National Institutes of Health. Availability of data and materials The study dataset is available from the corresponding author following institutional approvals. Ethics approval and consent to participate Institutional review boards at The Ohio State University and the Hanoi School of Public Health approved the study, and women provided written consent before enrolling. Consent for publication Not applicable. Competing interests The authors have no competing interests. Author details 1Division of Epidemiology, The Ohio State University, College of Public Health, Cunz Hall, 1841 Neil Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA. 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vinmec International Hospital, 458 Minh Khai, Hanoi, Vietnam. 3Department of Research and Training, Hanoi Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, La Thanh Street, Hanoi, Vietnam.Received: 11 June 2019 Accepted: 6 July 2020 References 1. Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, Sedgh G. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6: e380–9. 2. Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, Frick C. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:205–16. 3. Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39:18–38. 4. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plan. 2010;41:241–50. 5. Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE. Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:152–74. 6. Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Khatun M, Al Mamun A, Bor W, Clavarino A. A longitudinal study of child mental health and problem behaviours at 14 years of age following unplanned pregnancy. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:200–4. 7. Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324–508. 8. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. 9. Williamson LM, Buston K, Sweeting H. Young women's perceptions of pregnancy risk and use of emergency contraception: findings from a qualitative study. Contraception. 2009;79:310–5. 10. Motlaq ME, Eslami M, Yazdanpanah M, Nakhaee N. Contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in Iran. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121: 157–61. 11. Frohwirth L, Moore AM, Maniaci R. Perceptions of susceptibility to pregnancy among U.S. women obtaining abortions. Soc Sci Med. 2013;99:18–26. 12. Foster DG, Higgins JA, Karasek D, Ma S, Grossman D. Attitudes toward unprotected intercourse and risk of pregnancy among women seeking abortion. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22:e149–55. 13. Moreau C, Bohet A. Frequency and correlates of unintended pregnancy risk perceptions. Contraception. 2016;94:152–9. 14. Sinai I, Igras S, Lundgren R. A practical alternative to calculating unmet need for family planning. Open Access J Contracept. 2017;8:53–9. 15. Biggs MA, Foster DG. Misunderstanding the risk of conception from unprotected and protected sex. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23:e47–53. 16. World Health Organization, Johns Hopkins, United States Agency for International Development. Family planning: a global handbook for providers. 3rd ed; 2018. 17. Rahman M, Berenson AB, Herrera SR. Perceived susceptibility to pregnancy and its association with safer sex, contraceptive adherence and subsequent pregnancy among adolescent and young adult women. Contraception. 2013;87:437–42. 18. Hosmer D, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant R. Model building strategies and methods for logistic regression. In: Applied logistic regression. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013. p. 91–142. 19. Shelus V, VanEnk L, Giuffrida M, Jansen S, Connolly S, Mukabatsinda M, Jah F, Ndahindwa V, Shattuck D. Understanding your body matters: effects of an entertainment-education serial radio drama on fertility awareness in Rwanda. J Health Commun. 2018;23:761–72. 20. García D, Vassena R, Prat A, Vernaeve V. Increasing fertility knowledge and awareness by tailored education: a randomized controlled trial. Reprod BioMed Online. 2016;32:113–20. 21. García D, Rodríguez A, Vassena R. Actions to increase knowledge about age- related fertility decline in women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:371–8. 22. Anderson S, Frerichs L, Kaysin A, Wheeler SB, Halpern CT, Lich KH. Effects of two educational posters on contraceptive knowledge and intentions: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:53–62. 23. Balasch J, Gratacós E. Delayed childbearing: effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24:187–93.Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

File đính kèm:

underestimation_of_pregnancy_risk_among_women_in_viet_nam.pdf

underestimation_of_pregnancy_risk_among_women_in_viet_nam.pdf