The Vietnamese version of the health-related quality of life measure for children with epilepsy (cheqol-25): Reliability

Epilepsy is a chronic disease affecting humans since

ancient times and up to now, it remains as one of the

diseases that causes the most severe disabilities. Epilepsy

affects patients’ activities as well as their family for a long

lives [1]. Children with epilepsy are often more affected

psychologically and socially than children with asthma

although both are chronic diseases [2]. This shows that such

problems in children with epilepsy are not merely caused

by their living with a chronic medical condition [3]. Current

studies on epilepsy in the world in general and in Vietnam

in particular mostly still revolves around such classic

problems as pathophysiology or treatment effects without

paying adequate attention to the patients’ quality of life [4,

5]. Evaluation of epileptic patients’ lives provides important

information related to treatment and helps to improve

treatment quality [6].

In recent years, clinicians have paid more attention to

the health-related quality of life (HrQOL) issue of patients

with epilepsy and developed various instruments to assess

this factor. There are many studies on how to measure

HrQOL in adult and children with epilepsy in the world.

Recently, measurements of HrQOL have been accepted

to take not only a descriptive role but also instrument to

and management of epilepsy in patients [7].

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: The Vietnamese version of the health-related quality of life measure for children with epilepsy (cheqol-25): Reliability

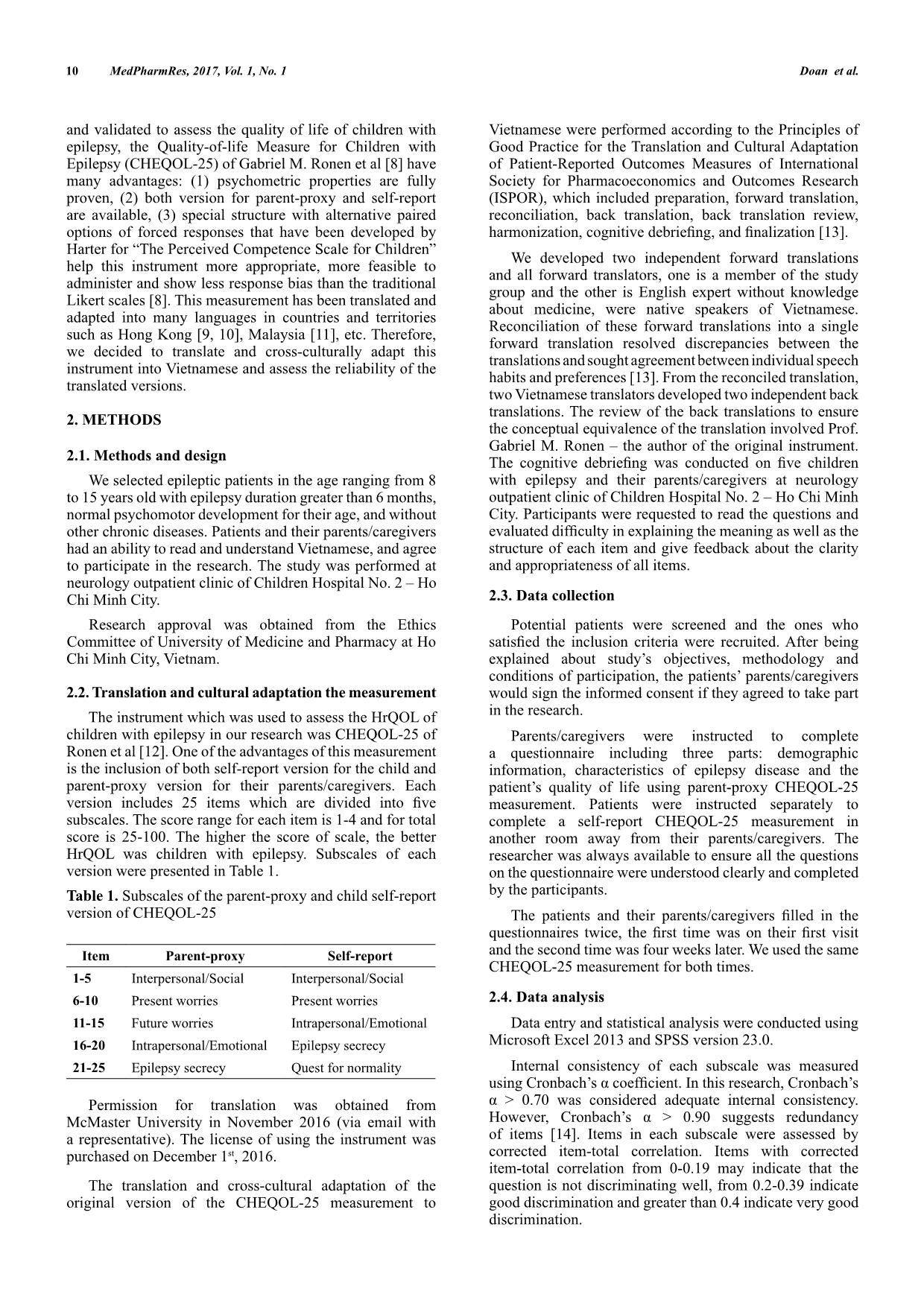

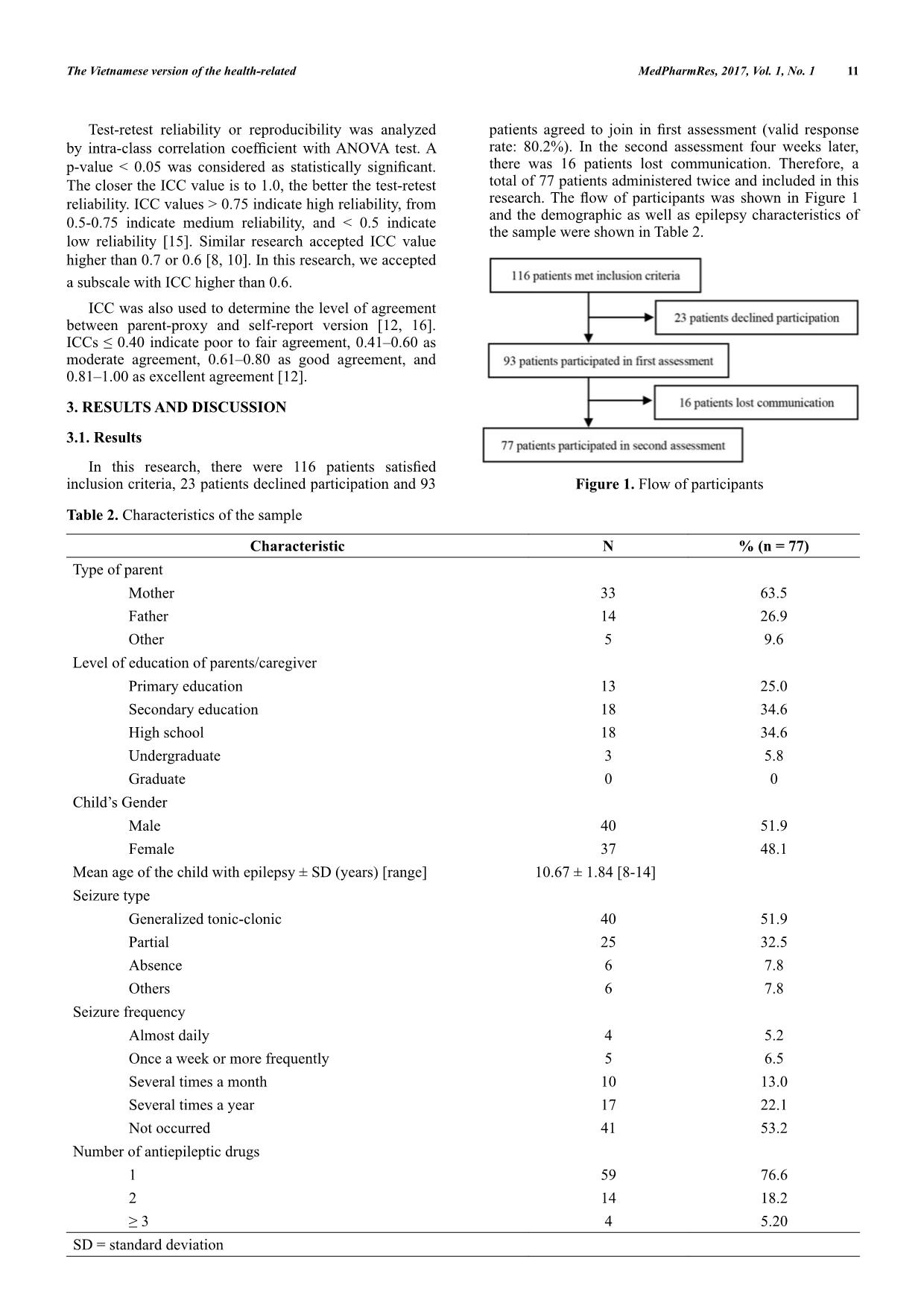

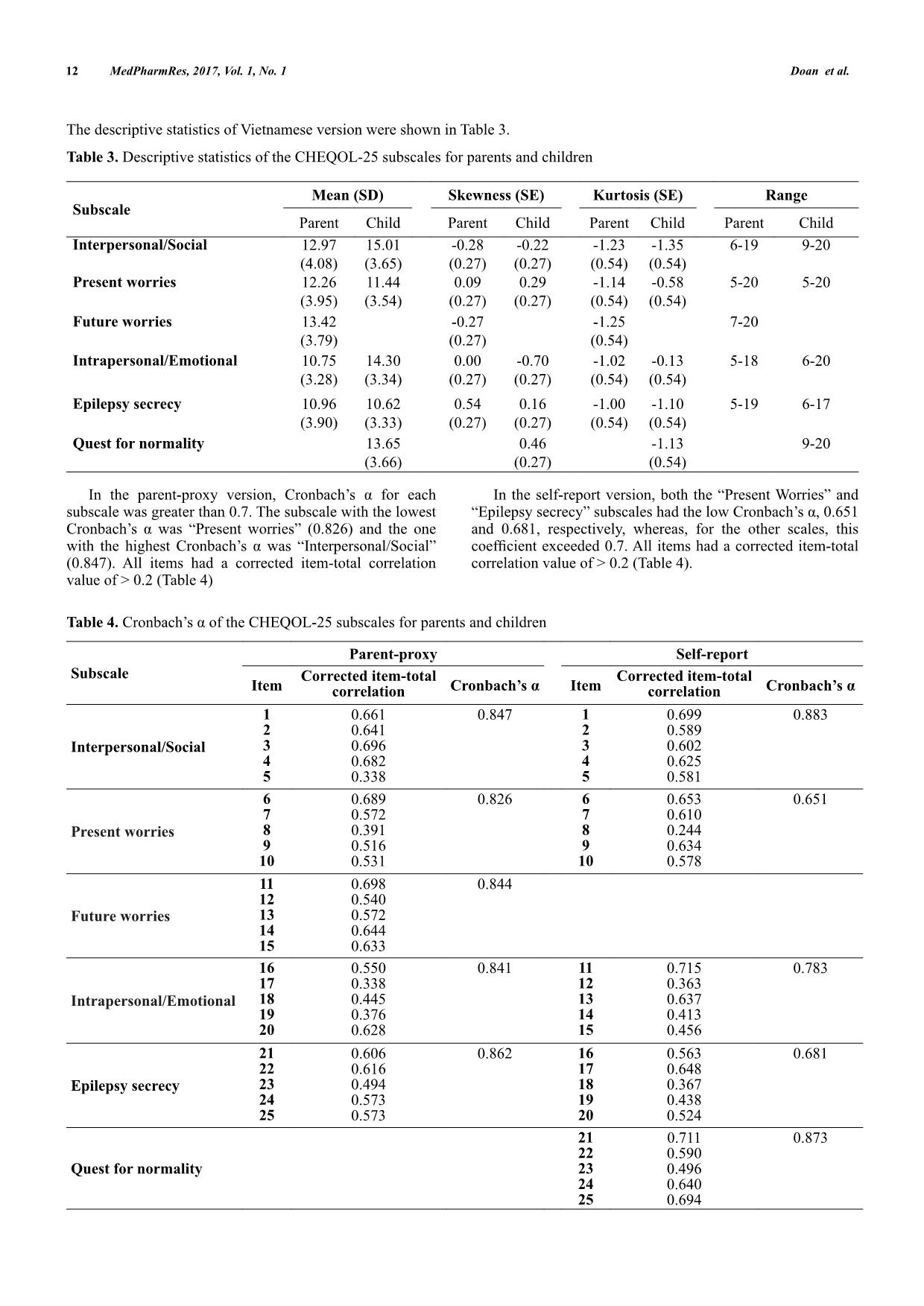

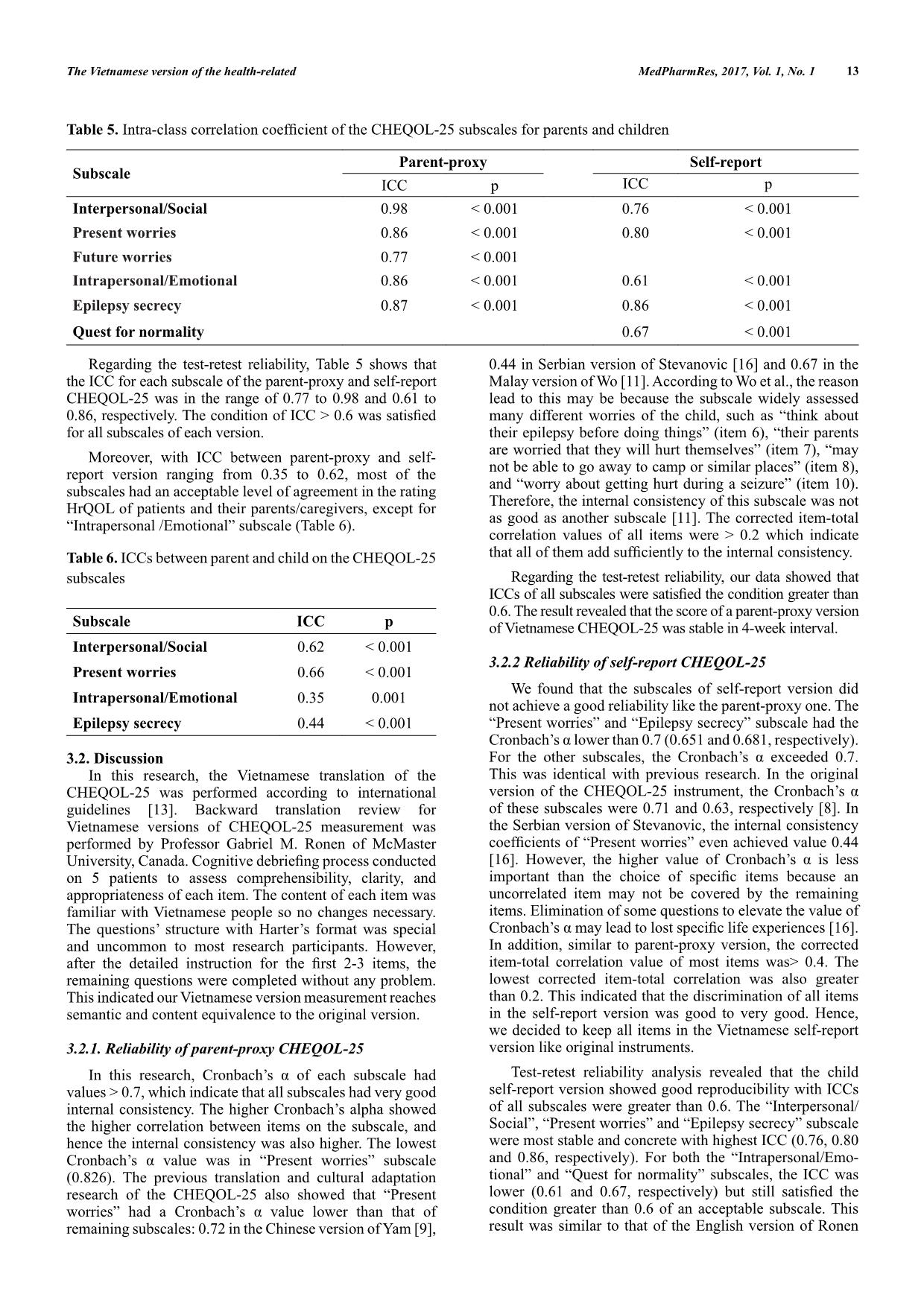

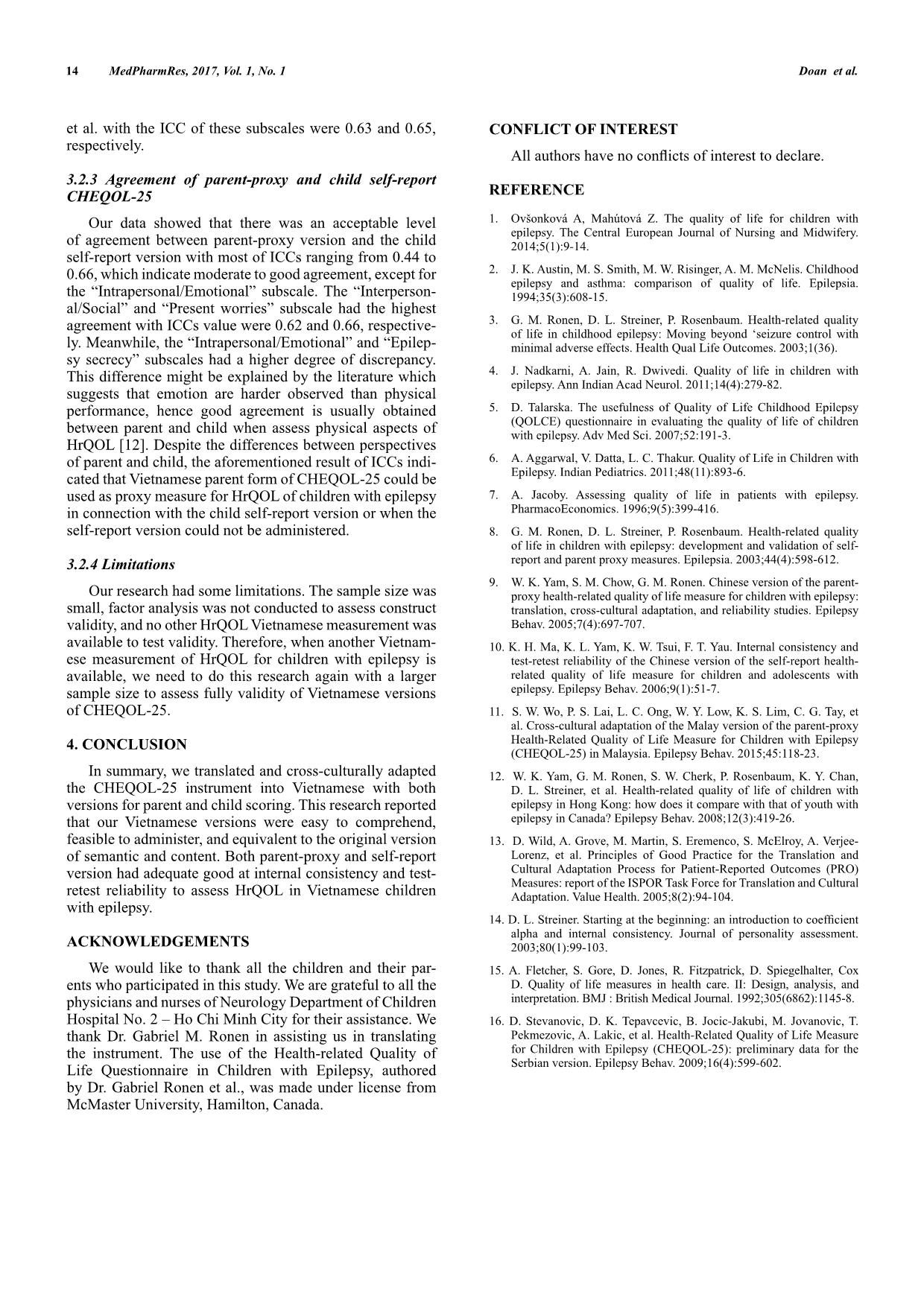

MedPharmRes, 2017, 1 9 MedPharmRes journal of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City homepage: and Original article The Vietnamese Version of the Health-related Quality of Life Measure for Children with Epilepsy (CHEQOL-25): Reliability Doan Huu Tria, Tran Diep Tuanb*, Nguyen Bao Huu Hanb a The Center for Advanced Training in Clinical Simulation, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; b Department of Pediatrics, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Received August 25, 2017: Accepted September 24, 2017 Published online December 10, 2017 Abstract: Purpose: This study aimed to translate and culturally adapt the self-report and parent-proxy Health-Related Quality of Life Measure for Children with Epilepsy (CHEQOL-25) into Vietnamese and to evaluate their reliability. Methods: Both English versions of the self-report and parent-proxy CHEQOL-25 were translated and culturally adapted into Vietnamese by using the Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process. The Vietnamese versions were scored by 77 epileptic patients, who aged 8–15 years, and their parents/caregivers at neurology outpatient clinic of Children Hospital No. 2 – Ho Chi Minh City. Reliability of the questionnaires was versions of the self-report and parent-proxy CHEQOL-25 were shown to be consistent with the English ones, easy to for each subscale of the Vietnamese version of the self-report and parent-proxy CHEQOL-25 was 0.65 to 0.86 and 0.83 to 0.86, respectively. The ICC for each subscale of the self-report and parent-proxy CHEQOL-25 was in the range of 0.61 to 0.86 and 0.77 to 0.98, respectively. Conclusion: The Vietnamese version of the self-report and Vietnamese version was shown to be reliable to assess the quality of life of children with epilepsy aged 8–15 years. Keywords: childhood epilepsy, quality of life, health-related quality of life, CHEQOL-25 instrument 1. INTRODUCTION Epilepsy is a chronic disease affecting humans since ancient times and up to now, it remains as one of the diseases that causes the most severe disabilities. Epilepsy affects patients’ activities as well as their family for a long lives [1]. Children with epilepsy are often more affected psychologically and socially than children with asthma although both are chronic diseases [2]. This shows that such problems in children with epilepsy are not merely caused by their living with a chronic medical condition [3]. Current studies on epilepsy in the world in general and in Vietnam in particular mostly still revolves around such classic problems as pathophysiology or treatment effects without paying adequate attention to the patients’ quality of life [4, 5]. Evaluation of epileptic patients’ lives provides important information related to treatment and helps to improve treatment quality [6]. In recent years, clinicians have paid more attention to the health-related quality of life (HrQOL) issue of patients with epilepsy and developed various instruments to assess this factor. There are many studies on how to measure HrQOL in adult and children with epilepsy in the world. Recently, measurements of HrQOL have been accepted to take not only a descriptive role but also instrument to and management of epilepsy in patients [7]. Quality of life, in general, is considered a social category, which is ruled by each country’s culture, tradition, and ideology. Therefore, results from the studies of other countries cannot absolutely apply to Vietnam society. In Vietnam today, there is still not a Vietnamese version of measurement of HrQOL in epileptic patients to be utilized locally. Among instruments have been developed * Address correspondence to this author at the Department of Pediatrics, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 217 Hong Bang street, District 5, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; E-mails: dieptuan@ump.edu.vn © 2017 MedPharmRes 10 MedPharmRes, 2017, Vol. 1, No. 1 Doan et al. and validated to assess the quality of life of children with epilepsy, the Quality-of-life Measure for Children with Epilepsy (CHEQOL-25) of Gabriel M. Ronen et al [8] have many advantages: (1) psychometric properties are fully proven, (2) both version for parent-proxy and self-report are available, (3) special structure with alternative paired options of forced responses that have been developed by Harter for “The Perceived Competence Scale for Children” help this instrument more appropriate, more feasible to administer and show less response bias than the traditional Likert scales [8]. This measurement has been translated and adapted into many languages in countries and territories such as Hong Kong [9, 10], Malaysia [11], etc. Therefore, we decided to translate and cross-culturally adapt this instrument into Vietnamese and assess the reliability of the translated ve ... tal correlation. Items with corrected item-total correlation from 0-0.19 may indicate that the question is not discriminating well, from 0.2-0.39 indicate good discrimination and greater than 0.4 indicate very good discrimination. 11The Vietnamese version of the health-related MedPharmRes, 2017, Vol. 1, No. 1 Test-retest reliability or reproducibility was analyzed The closer the ICC value is to 1.0, the better the test-retest reliability. ICC values > 0.75 indicate high reliability, from 0.5-0.75 indicate medium reliability, and < 0.5 indicate low reliability [15]. Similar research accepted ICC value higher than 0.7 or 0.6 [8, 10]. In this research, we accepted a subscale with ICC higher than 0.6. ICC was also used to determine the level of agreement between parent-proxy and self-report version [12, 16]. moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 as good agreement, and 0.81–1.00 as excellent agreement [12]. 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 3.1. Results inclusion criteria, 23 patients declined participation and 93 Table 2. Characteristics of the sample Characteristic N % (n = 77) Type of parent Mother 33 63.5 Father 14 26.9 Other 5 9.6 Level of education of parents/caregiver Primary education 13 25.0 Secondary education 18 34.6 High school 18 34.6 Undergraduate 3 5.8 Graduate 0 0 Child’s Gender Male 40 51.9 Female 37 48.1 Mean age of the child with epilepsy ± SD (years) [range] 10.67 ± 1.84 [8-14] Seizure type Generalized tonic-clonic 40 51.9 Partial 25 32.5 Absence 6 7.8 Others 6 7.8 Seizure frequency Almost daily 4 5.2 Once a week or more frequently 5 6.5 Several times a month 10 13.0 Several times a year 17 22.1 Not occurred 41 53.2 Number of antiepileptic drugs 1 59 76.6 2 14 18.2 4 5.20 SD = standard deviation rate: 80.2%). In the second assessment four weeks later, there was 16 patients lost communication. Therefore, a total of 77 patients administered twice and included in this and the demographic as well as epilepsy characteristics of the sample were shown in Table 2. Figure 1. Flow of participants 12 The descriptive statistics of Vietnamese version were shown in Table 3. Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the CHEQOL-25 subscales for parents and children Subscale Mean (SD) Skewness (SE) Kurtosis (SE) Range Parent Child Parent Child Parent Child Parent Child Interpersonal/Social 12.97 (4.08) 15.01 (3.65) -0.28 (0.27) -0.22 (0.27) -1.23 (0.54) -1.35 (0.54) 6-19 9-20 Present worries 12.26 (3.95) 11.44 (3.54) 0.09 (0.27) 0.29 (0.27) -1.14 (0.54) -0.58 (0.54) 5-20 5-20 Future worries 13.42 (3.79) -0.27 (0.27) -1.25 (0.54) 7-20 Intrapersonal/Emotional 10.75 (3.28) 14.30 (3.34) 0.00 (0.27) -0.70 (0.27) -1.02 (0.54) -0.13 (0.54) 5-18 6-20 Epilepsy secrecy 10.96 (3.90) 10.62 (3.33) 0.54 (0.27) 0.16 (0.27) -1.00 (0.54) -1.10 (0.54) 5-19 6-17 Quest for normality 13.65 (3.66) 0.46 (0.27) -1.13 (0.54) 9-20 subscale was greater than 0.7. The subscale with the lowest (0.847). All items had a corrected item-total correlation value of > 0.2 (Table 4) In the self-report version, both the “Present Worries” and and 0.681, respectively, whereas, for the other scales, this correlation value of > 0.2 (Table 4). Table 4. Subscale Parent-proxy Self-report Item Corrected item-total correlation Item Corrected item-total correlation Interpersonal/Social 1 2 3 4 5 0.661 0.641 0.696 0.682 0.338 0.847 1 2 3 4 5 0.699 0.589 0.602 0.625 0.581 0.883 Present worries 6 7 8 9 10 0.689 0.572 0.391 0.516 0.531 0.826 6 7 8 9 10 0.653 0.610 0.244 0.634 0.578 0.651 Future worries 11 12 13 14 15 0.698 0.540 0.572 0.644 0.633 0.844 Intrapersonal/Emotional 16 17 18 19 20 0.550 0.338 0.445 0.376 0.628 0.841 11 12 13 14 15 0.715 0.363 0.637 0.413 0.456 0.783 Epilepsy secrecy 21 22 23 24 25 0.606 0.616 0.494 0.573 0.573 0.862 16 17 18 19 20 0.563 0.648 0.367 0.438 0.524 0.681 Quest for normality 21 22 23 24 25 0.711 0.590 0.496 0.640 0.694 0.873 MedPharmRes, 2017, Vol. 1, No. 1 Doan et al. 13 Table 5. Subscale Parent-proxy Self-report ICC p ICC p Interpersonal/Social 0.98 < 0.001 0.76 < 0.001 Present worries 0.86 < 0.001 0.80 < 0.001 Future worries 0.77 < 0.001 Intrapersonal/Emotional 0.86 < 0.001 0.61 < 0.001 Epilepsy secrecy 0.87 < 0.001 0.86 < 0.001 Quest for normality 0.67 < 0.001 Regarding the test-retest reliability, Table 5 shows that the ICC for each subscale of the parent-proxy and self-report CHEQOL-25 was in the range of 0.77 to 0.98 and 0.61 to for all subscales of each version. Moreover, with ICC between parent-proxy and self- report version ranging from 0.35 to 0.62, most of the subscales had an acceptable level of agreement in the rating HrQOL of patients and their parents/caregivers, except for “Intrapersonal /Emotional” subscale (Table 6). Table 6. ICCs between parent and child on the CHEQOL-25 subscales Subscale ICC p Interpersonal/Social 0.62 < 0.001 Present worries 0.66 < 0.001 Intrapersonal/Emotional 0.35 0.001 Epilepsy secrecy 0.44 < 0.001 3.2. Discussion In this research, the Vietnamese translation of the CHEQOL-25 was performed according to international guidelines [13]. Backward translation review for Vietnamese versions of CHEQOL-25 measurement was performed by Professor Gabriel M. Ronen of McMaster on 5 patients to assess comprehensibility, clarity, and appropriateness of each item. The content of each item was familiar with Vietnamese people so no changes necessary. The questions’ structure with Harter’s format was special and uncommon to most research participants. However, remaining questions were completed without any problem. This indicated our Vietnamese version measurement reaches semantic and content equivalence to the original version. 3.2.1. Reliability of parent-proxy CHEQOL-25 values > 0.7, which indicate that all subscales had very good internal consistency. The higher Cronbach’s alpha showed the higher correlation between items on the subscale, and hence the internal consistency was also higher. The lowest (0.826). The previous translation and cultural adaptation research of the CHEQOL-25 also showed that “Present remaining subscales: 0.72 in the Chinese version of Yam [9], 0.44 in Serbian version of Stevanovic [16] and 0.67 in the Malay version of Wo [11]. According to Wo et al., the reason lead to this may be because the subscale widely assessed many different worries of the child, such as “think about their epilepsy before doing things” (item 6), “their parents are worried that they will hurt themselves” (item 7), “may not be able to go away to camp or similar places” (item 8), and “worry about getting hurt during a seizure” (item 10). Therefore, the internal consistency of this subscale was not as good as another subscale [11]. The corrected item-total correlation values of all items were > 0.2 which indicate Regarding the test-retest reliability, our data showed that 0.6. The result revealed that the score of a parent-proxy version of Vietnamese CHEQOL-25 was stable in 4-week interval. 3.2.2 Reliability of self-report CHEQOL-25 We found that the subscales of self-report version did not achieve a good reliability like the parent-proxy one. The “Present worries” and “Epilepsy secrecy” subscale had the This was identical with previous research. In the original of these subscales were 0.71 and 0.63, respectively [8]. In the Serbian version of Stevanovic, the internal consistency uncorrelated item may not be covered by the remaining items. Elimination of some questions to elevate the value of In addition, similar to parent-proxy version, the corrected item-total correlation value of most items was> 0.4. The lowest corrected item-total correlation was also greater than 0.2. This indicated that the discrimination of all items in the self-report version was good to very good. Hence, we decided to keep all items in the Vietnamese self-report version like original instruments. Test-retest reliability analysis revealed that the child self-report version showed good reproducibility with ICCs of all subscales were greater than 0.6. The “Interpersonal/ Social”, “Present worries” and “Epilepsy secrecy” subscale were most stable and concrete with highest ICC (0.76, 0.80 and 0.86, respectively). For both the “Intrapersonal/Emo- tional” and “Quest for normality” subscales, the ICC was condition greater than 0.6 of an acceptable subscale. This result was similar to that of the English version of Ronen The Vietnamese version of the health-related MedPharmRes, 2017, Vol. 1, No. 1 14 MedPharmRes, 2017, Vol. 1, No. 1 Doan et al. et al. with the ICC of these subscales were 0.63 and 0.65, respectively. 3.2.3 Agreement of parent-proxy and child self-report CHEQOL-25 Our data showed that there was an acceptable level of agreement between parent-proxy version and the child self-report version with most of ICCs ranging from 0.44 to 0.66, which indicate moderate to good agreement, except for the “Intrapersonal/Emotional” subscale. The “Interperson- al/Social” and “Present worries” subscale had the highest agreement with ICCs value were 0.62 and 0.66, respective- ly. Meanwhile, the “Intrapersonal/Emotional” and “Epilep- sy secrecy” subscales had a higher degree of discrepancy. This difference might be explained by the literature which suggests that emotion are harder observed than physical performance, hence good agreement is usually obtained between parent and child when assess physical aspects of HrQOL [12]. Despite the differences between perspectives of parent and child, the aforementioned result of ICCs indi- cated that Vietnamese parent form of CHEQOL-25 could be used as proxy measure for HrQOL of children with epilepsy in connection with the child self-report version or when the self-report version could not be administered. 3.2.4 Limitations Our research had some limitations. The sample size was small, factor analysis was not conducted to assess construct validity, and no other HrQOL Vietnamese measurement was available to test validity. Therefore, when another Vietnam- ese measurement of HrQOL for children with epilepsy is available, we need to do this research again with a larger sample size to assess fully validity of Vietnamese versions of CHEQOL-25. 4. CONCLUSION In summary, we translated and cross-culturally adapted the CHEQOL-25 instrument into Vietnamese with both versions for parent and child scoring. This research reported that our Vietnamese versions were easy to comprehend, feasible to administer, and equivalent to the original version of semantic and content. Both parent-proxy and self-report version had adequate good at internal consistency and test- retest reliability to assess HrQOL in Vietnamese children with epilepsy. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank all the children and their par- ents who participated in this study. We are grateful to all the physicians and nurses of Neurology Department of Children Hospital No. 2 – Ho Chi Minh City for their assistance. We thank Dr. Gabriel M. Ronen in assisting us in translating the instrument. The use of the Health-related Quality of Life Questionnaire in Children with Epilepsy, authored by Dr. Gabriel Ronen et al., was made under license from McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. CONFLICT OF INTEREST REFERENCE 1. Ovšonková A, Mahútová Z. The quality of life for children with epilepsy. The Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery. 2014;5(1):9-14. 2. J. K. Austin, M. S. Smith, M. W. Risinger, A. M. McNelis. Childhood epilepsy and asthma: comparison of quality of life. Epilepsia. 1994;35(3):608-15. 3. G. M. Ronen, D. L. Streiner, P. Rosenbaum. Health-related quality of life in childhood epilepsy: Moving beyond ‘seizure control with minimal adverse effects. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(36). 4. J. Nadkarni, A. Jain, R. Dwivedi. Quality of life in children with epilepsy. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14(4):279-82. 5. D. Talarska. The usefulness of Quality of Life Childhood Epilepsy (QOLCE) questionnaire in evaluating the quality of life of children with epilepsy. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52:191-3. 6. A. Aggarwal, V. Datta, L. C. Thakur. Quality of Life in Children with Epilepsy. Indian Pediatrics. 2011;48(11):893-6. 7. A. Jacoby. Assessing quality of life in patients with epilepsy. PharmacoEconomics. 1996;9(5):399-416. 8. G. M. Ronen, D. L. Streiner, P. Rosenbaum. Health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy: development and validation of self- report and parent proxy measures. Epilepsia. 2003;44(4):598-612. 9. W. K. Yam, S. M. Chow, G. M. Ronen. Chinese version of the parent- proxy health-related quality of life measure for children with epilepsy: translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and reliability studies. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(4):697-707. 10. K. H. Ma, K. L. Yam, K. W. Tsui, F. T. Yau. Internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the Chinese version of the self-report health- related quality of life measure for children and adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9(1):51-7. 11. S. W. Wo, P. S. Lai, L. C. Ong, W. Y. Low, K. S. Lim, C. G. Tay, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Malay version of the parent-proxy Health-Related Quality of Life Measure for Children with Epilepsy (CHEQOL-25) in Malaysia. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;45:118-23. 12. W. K. Yam, G. M. Ronen, S. W. Cherk, P. Rosenbaum, K. Y. Chan, D. L. Streiner, et al. Health-related quality of life of children with epilepsy in Hong Kong: how does it compare with that of youth with epilepsy in Canada? Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(3):419-26. 13. D. Wild, A. Grove, M. Martin, S. Eremenco, S. McElroy, A. Verjee- Lorenz, et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94-104. alpha and internal consistency. Journal of personality assessment. 2003;80(1):99-103. 15. A. Fletcher, S. Gore, D. Jones, R. Fitzpatrick, D. Spiegelhalter, Cox D. Quality of life measures in health care. II: Design, analysis, and interpretation. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 1992;305(6862):1145-8. 16. D. Stevanovic, D. K. Tepavcevic, B. Jocic-Jakubi, M. Jovanovic, T. Pekmezovic, A. Lakic, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Measure for Children with Epilepsy (CHEQOL-25): preliminary data for the Serbian version. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;16(4):599-602.

File đính kèm:

the_vietnamese_version_of_the_health_related_quality_of_life.pdf

the_vietnamese_version_of_the_health_related_quality_of_life.pdf