The use of linguistic units and their implicatures in the listening section of toefl iBT test

ABSTRACT

Implicature is a means of conveying what speakers mean linguistically, and it is most commonly used in

spoken language. Identifying the possible interpretations and discovering the implied meanings of the information,

nevertheless, are really challenging for non-native English speakers, especially for ESL/EFL test-takers who are

under testing pressure. This descriptive study, therefore, aimed to quantitatively and qualitatively explore the

language units and their implicatures used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT (Test of English as a Foreign

Language versioned Internet-based test). A corpus consisting of 87 lectures, 97 long conversations, and 31 short

conversations/adjacency pairs that were sourced from TOEFL iBT materials was developed. The framework

employed to analyze data was based on the initial lists of triggers proposed by Gazdar (1979), Grice (1978),

Levinson (1993), and Yule (1996). The findings reveal that linking words are the most common linguistic units

while set phrases are the least common ones that are used to trigger implicatures in the listening section of TOEFL

iBT materials. Additionally, diverse implicatures of linguistic units used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT are

uncovered.

Keywords: Implicature; Language unit; Listening; TOEFL iBT.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: The use of linguistic units and their implicatures in the listening section of toefl iBT test

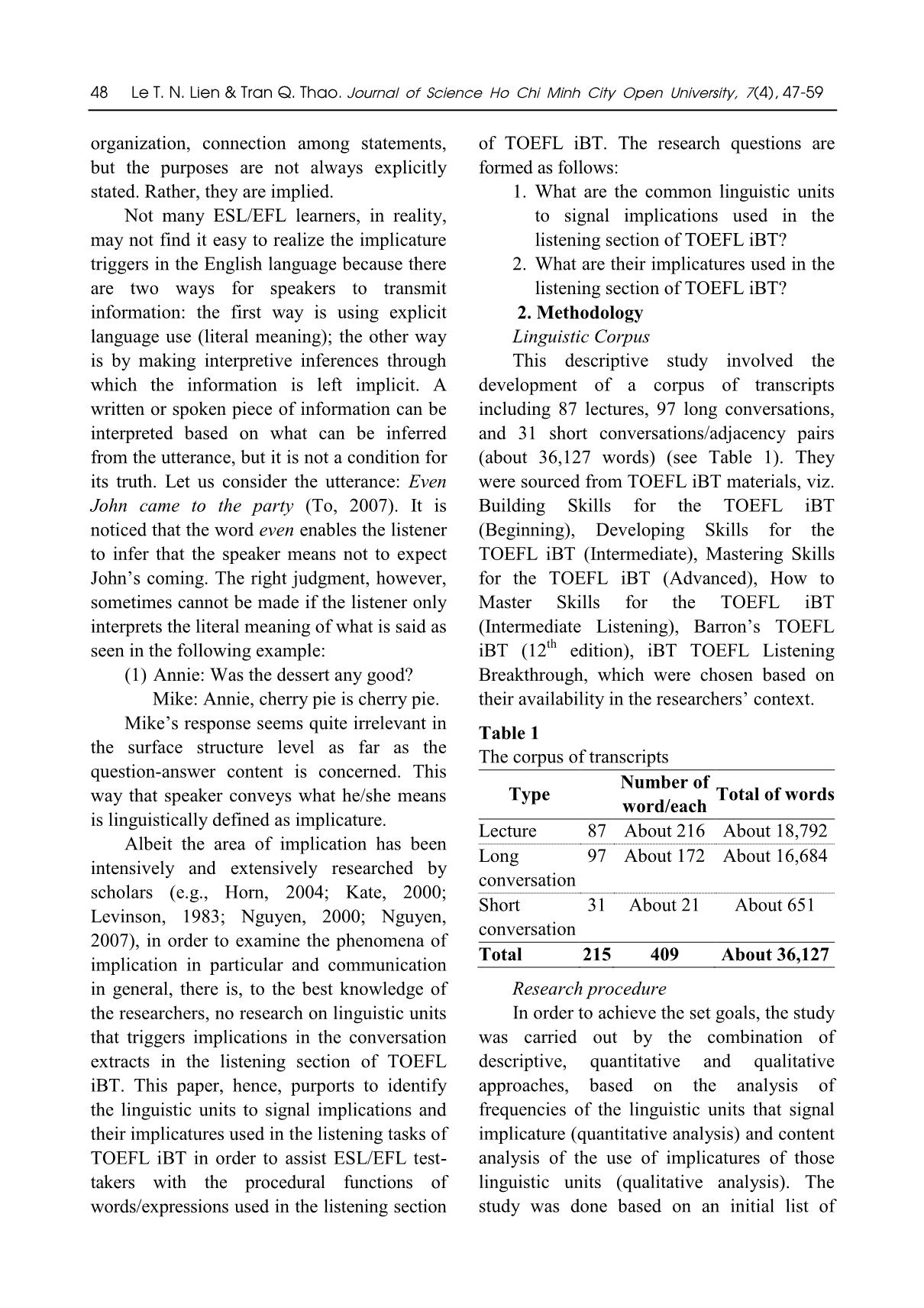

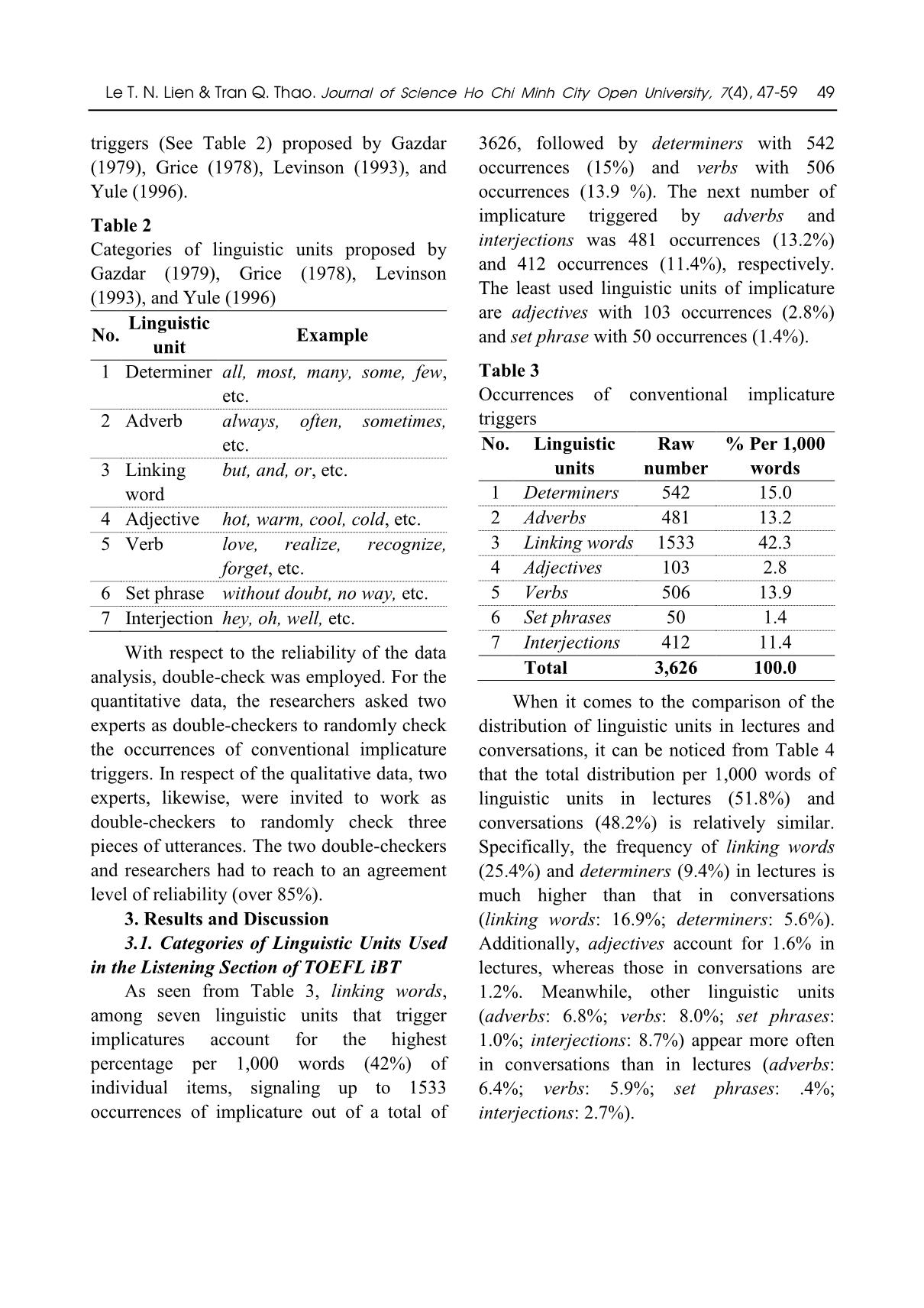

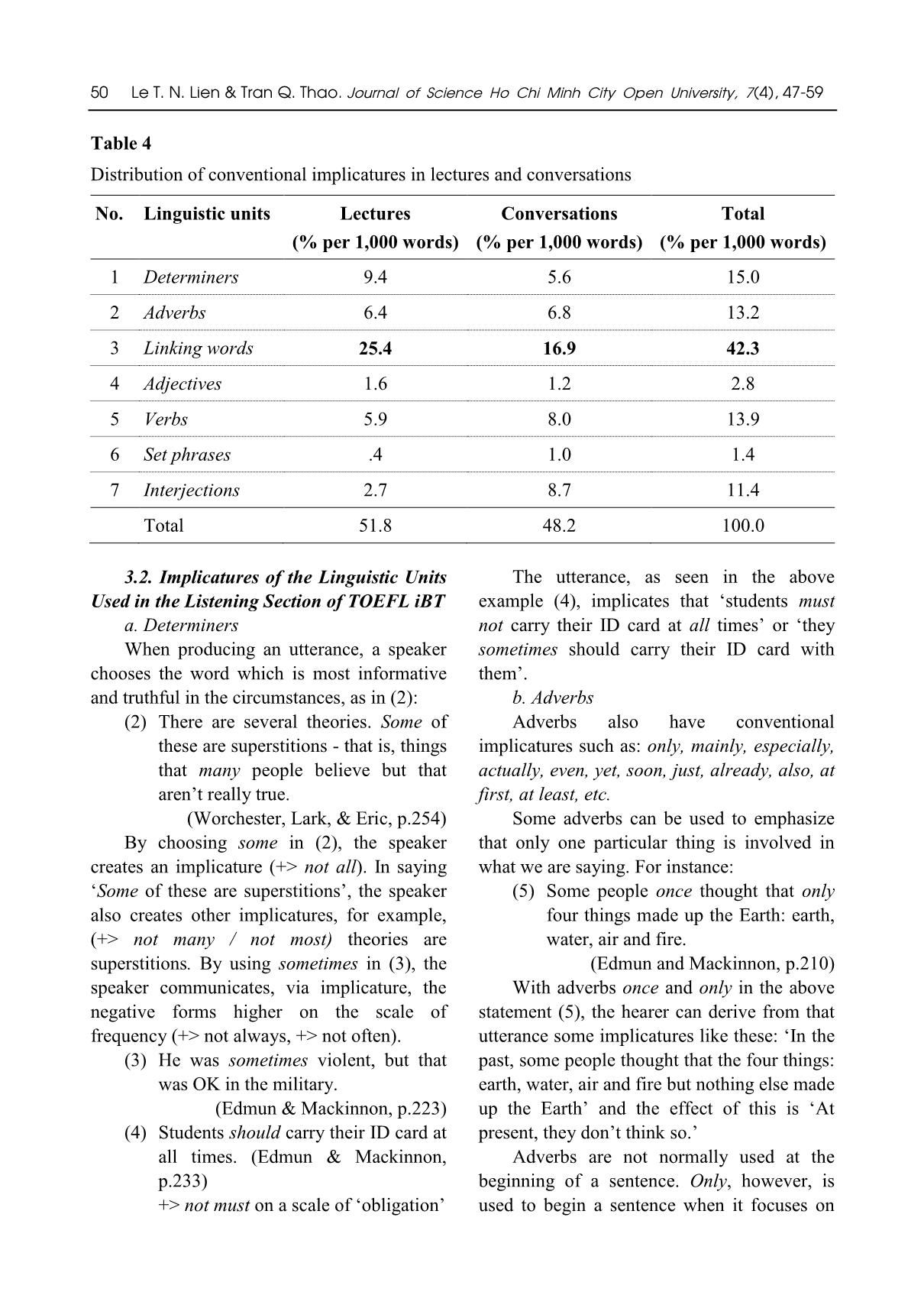

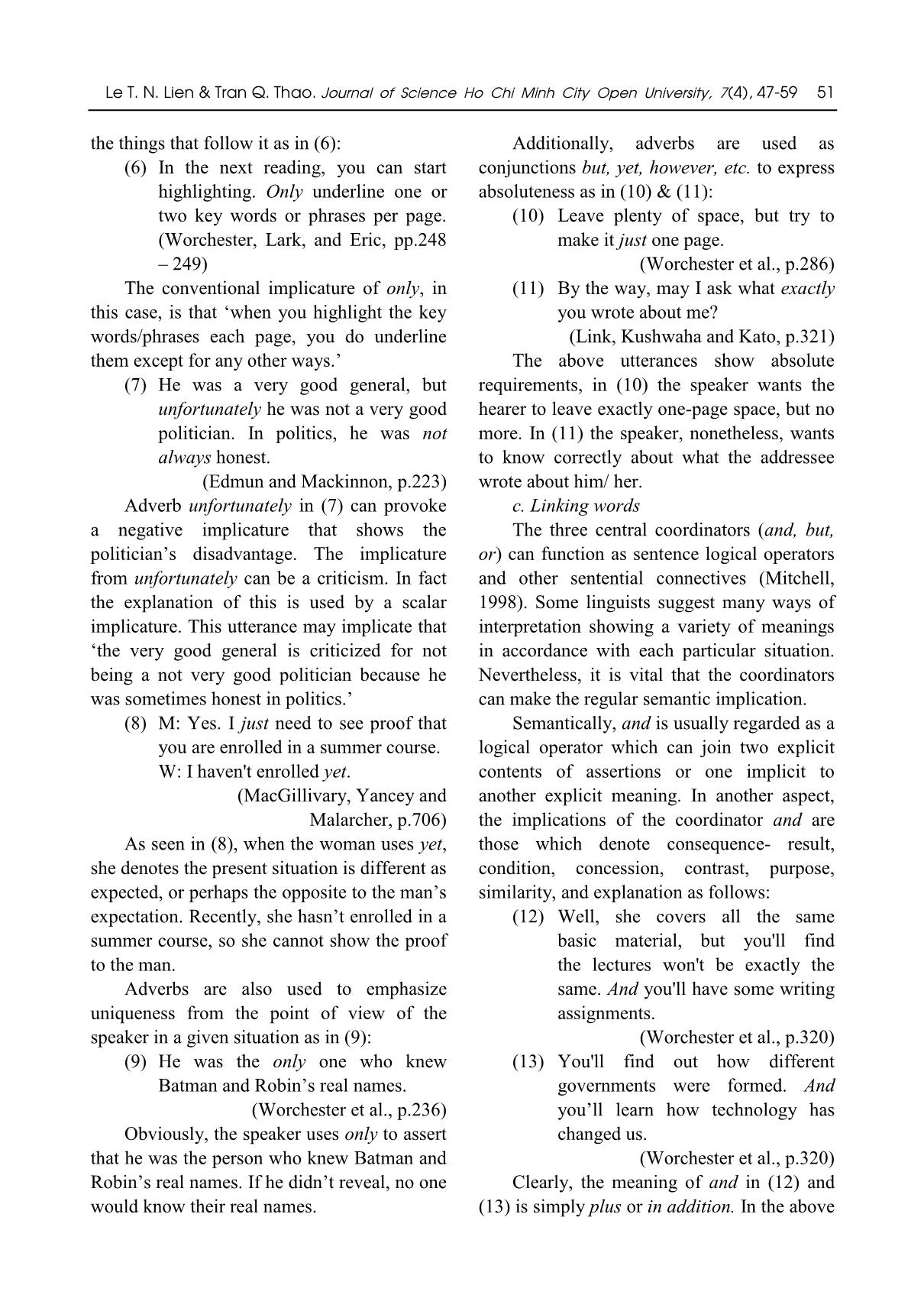

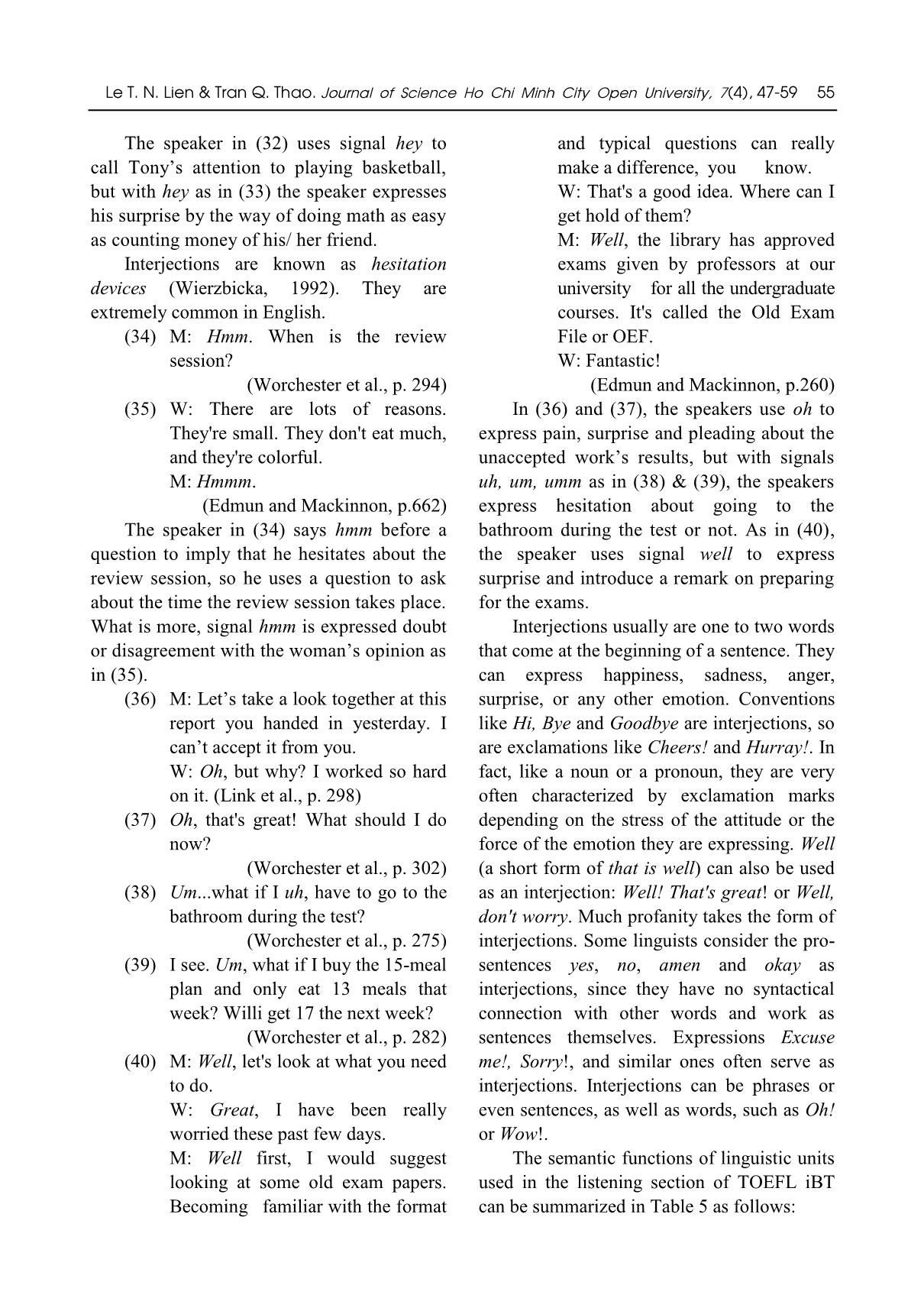

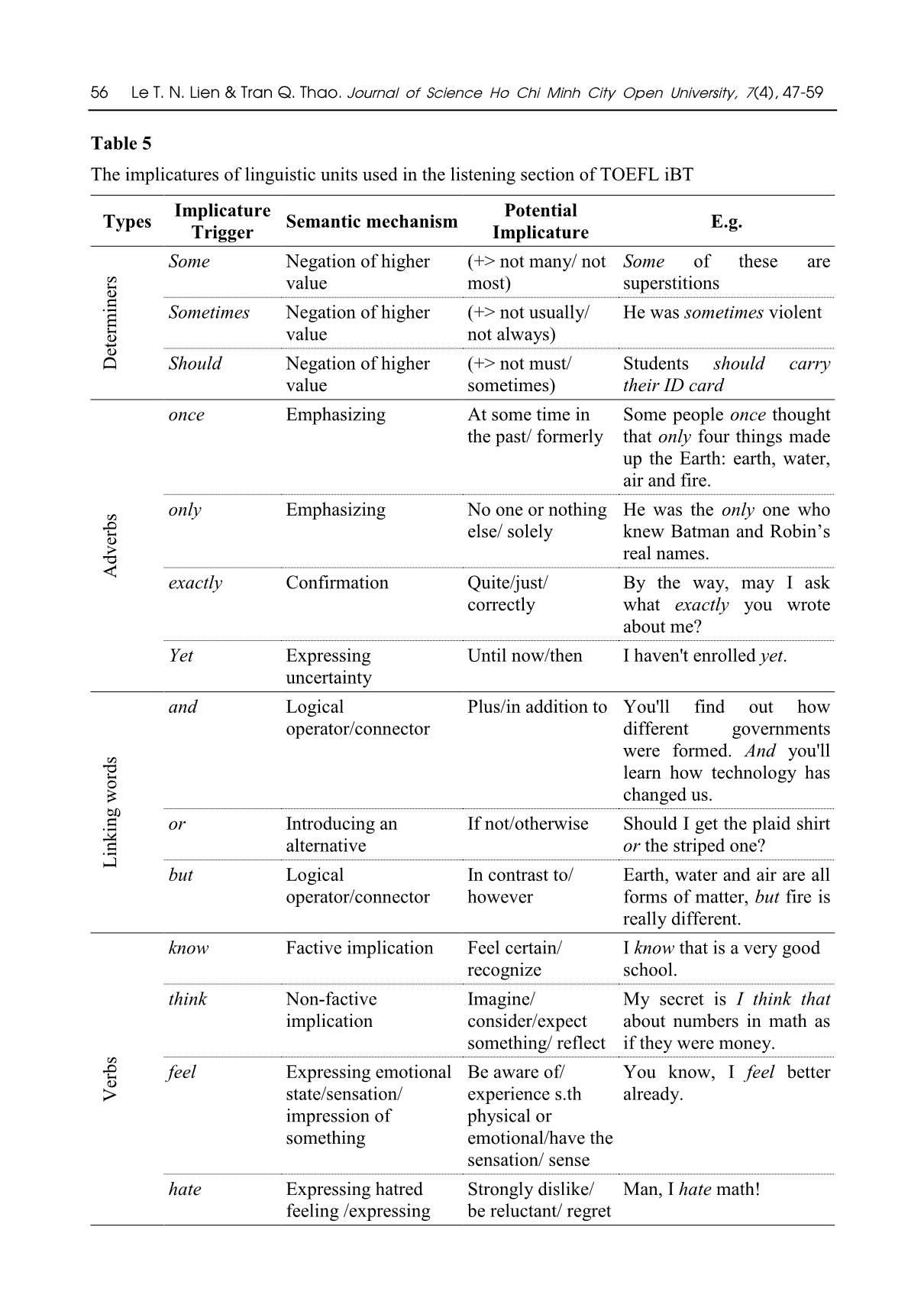

Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 47 THE USE OF LINGUISTIC UNITS AND THEIR IMPLICATURES IN THE LISTENING SECTION OF TOEFL iBT TEST LE THI NHU LIEN Dak Lak Teacher Training College, Vietnam - lethinhulien@gmail.com TRAN QUOC THAO Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology, Vietnam - tq.thao@hutech.edu.vn (Received: July 30, 2017; Revised: August 28, 2017; Accepted: November 29, 2017) ABSTRACT Implicature is a means of conveying what speakers mean linguistically, and it is most commonly used in spoken language. Identifying the possible interpretations and discovering the implied meanings of the information, nevertheless, are really challenging for non-native English speakers, especially for ESL/EFL test-takers who are under testing pressure. This descriptive study, therefore, aimed to quantitatively and qualitatively explore the language units and their implicatures used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT (Test of English as a Foreign Language versioned Internet-based test). A corpus consisting of 87 lectures, 97 long conversations, and 31 short conversations/adjacency pairs that were sourced from TOEFL iBT materials was developed. The framework employed to analyze data was based on the initial lists of triggers proposed by Gazdar (1979), Grice (1978), Levinson (1993), and Yule (1996). The findings reveal that linking words are the most common linguistic units while set phrases are the least common ones that are used to trigger implicatures in the listening section of TOEFL iBT materials. Additionally, diverse implicatures of linguistic units used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT are uncovered. Keywords: Implicature; Language unit; Listening; TOEFL iBT. 1. Introduction Since the English language has been long adopted as the medium of instruction throughout the world, ESL/EFL learners have to take different types of English language test in order to gain the admission requirements to study at universities or colleges in terms of English language proficiency. The standardized Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) versioned Internet-based test (iBT), emphasizing integrated communicative skills and communicative competence, is of those designed to assess English language skills of non-native speakers and to be taken on the Internet, (ETS, 2015). It is not meant to test academic knowledge or computer ability, and as such, questions are always based on materials found in the test. It is, however, agreed that the TOEFL iBT test is challenging, especially the listening task. Listening, according to ETS (2007), is one of the most important skills necessary for success on TOEFL iBT and in academics in general. The listening section measures test- takers’ ability to understand spoken English from North America and other English- speaking parts of the world. Test-takers have to listen to a wide range of lectures and conversations in academic environments, in which the speech sounds very natural. Moreover, there are nine types of questions in the listening section, namely, Gist-Content, Gist-Purpose, Detail, Understanding the Function of What is Said, Understanding the Speaker’s Attitude, Understanding Organization, Connecting Content and Making Inferences (ETS, 2007). One of the most challenging types of question in the listening section of TOEFL test is inference since test- takers may have to infer an opinion, attitude, 48 Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 organization, connection among statements, but the purposes are not always explicitly stated. Rather, they are implied. Not many ESL/EFL learners, in reality, may not find it easy to realize the implicature triggers in the English language because there are two ways for speakers to transmit information: the first way is using explicit language use (literal meaning); the other way is by making interpretive inferences through which the information is left implicit. A written or spoken piece of information can be interpreted based on what can be inferred from the utterance, but it is not a condition for its truth. Let us consider the utterance: Even John came to the party (To, 2007). It is noticed that the word even enables the listener to infer that the speaker means not to expect John’s coming. The right judgment, however, sometimes cannot be made if the listener only interprets the literal meaning of what is said as seen in the following example: (1) Annie: Was the dessert any good? Mike: Annie, cherry pie is cherry pie. Mike’s response seems quite irrelevant in the surface structure level as far as the question-answer content is concerned. This way that speaker conveys what he/she means is linguistically defined as implicature. Albeit the area of imp ... up of words that have a particular meaning for a circumstance, and it may be a phrasal verb, idiomatic phrases, or idioms that typically refer to expressions where the figurative meaning of the statement cannot be guessed from the individual words. Yet the speaker, habitually, uses it as a regime. Let us examine the following examples: (28) W: Today, we'll talk about the most important things in management. In a nut shell, that means how to make things run smoothly. (Edmun and Mackinnon, p. 288) (29) M: Is the lecture tonight worth attending? W: Without doubt. (Jessop, p.206) (30) M: Do you think Professor Simpson will cancel class on account of the special conference? W: Not likely. (Jessop, p.213) (31) M: Do you think Mary will get there on time? W: No way. (Jessop, p.221) The woman in (28) uses In a nut shell to summarize her point instead of using briefly, in summary, lastly, etc.. As far as the utterance (29) is concerned, by saying Without doubt, the woman, believes the talk will be valuable. In respect of (30), with set phrase Not likely, the woman in (30), means she doubts class will be canceled. Similarly, with No way, the woman means Mary will be late as in (31). g. Interjections Interjections do not encode conceptual but procedural meaning. Accordingly, the type of interjections that has labeled as emotive or expressive interjections lead the hearer to embed a proposition they accompany under a propositional-attitude description, which the hearer can exploit so as to grasp the attitude expressed by the speaker toward the proposition communicated. On the other hand, in those cases in which interjections appear alone constituting an independent utterance and do not accompany a proposition, these interjections provide the hearer with a vague idea of the speaker’s feelings or emotions. In fact, interjections behave like sentences: they correspond to communicative units (utterances) which can be syntactically autonomous, and intonationally and semantically complete. In addition, they are highly context dependent as, strictly speaking, they do not have so-called lexical meaning but express pragmatic meanings such as surprise, joy, pain, etc. For examples: (32) Hey, Tony. Want to go play basketball? (Worchester et al, p. 228) (33) Hey, that’s awesome! I’ll try it tomorrow. Thanks. (Worchester et al., p. 255) Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 55 The speaker in (32) uses signal hey to call Tony’s attention to playing basketball, but with hey as in (33) the speaker expresses his surprise by the way of doing math as easy as counting money of his/ her friend. Interjections are known as hesitation devices (Wierzbicka, 1992). They are extremely common in English. (34) M: Hmm. When is the review session? (Worchester et al., p. 294) (35) W: There are lots of reasons. They're small. They don't eat much, and they're colorful. M: Hmmm. (Edmun and Mackinnon, p.662) The speaker in (34) says hmm before a question to imply that he hesitates about the review session, so he uses a question to ask about the time the review session takes place. What is more, signal hmm is expressed doubt or disagreement with the woman’s opinion as in (35). (36) M: Let’s take a look together at this report you handed in yesterday. I can’t accept it from you. W: Oh, but why? I worked so hard on it. (Link et al., p. 298) (37) Oh, that's great! What should I do now? (Worchester et al., p. 302) (38) Um...what if I uh, have to go to the bathroom during the test? (Worchester et al., p. 275) (39) I see. Um, what if I buy the 15-meal plan and only eat 13 meals that week? Willi get 17 the next week? (Worchester et al., p. 282) (40) M: Well, let's look at what you need to do. W: Great, I have been really worried these past few days. M: Well first, I would suggest looking at some old exam papers. Becoming familiar with the format and typical questions can really make a difference, you know. W: That's a good idea. Where can I get hold of them? M: Well, the library has approved exams given by professors at our university for all the undergraduate courses. It's called the Old Exam File or OEF. W: Fantastic! (Edmun and Mackinnon, p.260) In (36) and (37), the speakers use oh to express pain, surprise and pleading about the unaccepted work’s results, but with signals uh, um, umm as in (38) & (39), the speakers express hesitation about going to the bathroom during the test or not. As in (40), the speaker uses signal well to express surprise and introduce a remark on preparing for the exams. Interjections usually are one to two words that come at the beginning of a sentence. They can express happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, or any other emotion. Conventions like Hi, Bye and Goodbye are interjections, so are exclamations like Cheers! and Hurray!. In fact, like a noun or a pronoun, they are very often characterized by exclamation marks depending on the stress of the attitude or the force of the emotion they are expressing. Well (a short form of that is well) can also be used as an interjection: Well! That's great! or Well, don't worry. Much profanity takes the form of interjections. Some linguists consider the pro- sentences yes, no, amen and okay as interjections, since they have no syntactical connection with other words and work as sentences themselves. Expressions Excuse me!, Sorry!, and similar ones often serve as interjections. Interjections can be phrases or even sentences, as well as words, such as Oh! or Wow!. The semantic functions of linguistic units used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT can be summarized in Table 5 as follows: 56 Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 Table 5 The implicatures of linguistic units used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT Types Implicature Trigger Semantic mechanism Potential Implicature E.g. D et er m in er s Some Negation of higher value (+> not many/ not most) Some of these are superstitions Sometimes Negation of higher value (+> not usually/ not always) He was sometimes violent Should Negation of higher value (+> not must/ sometimes) Students should carry their ID card A d v er b s once Emphasizing At some time in the past/ formerly Some people once thought that only four things made up the Earth: earth, water, air and fire. only Emphasizing No one or nothing else/ solely He was the only one who knew Batman and Robin’s real names. exactly Confirmation Quite/just/ correctly By the way, may I ask what exactly you wrote about me? Yet Expressing uncertainty Until now/then I haven't enrolled yet. L in k in g w o rd s and Logical operator/connector Plus/in addition to You'll find out how different governments were formed. And you'll learn how technology has changed us. or Introducing an alternative If not/otherwise Should I get the plaid shirt or the striped one? but Logical operator/connector In contrast to/ however Earth, water and air are all forms of matter, but fire is really different. V er b s know Factive implication Feel certain/ recognize I know that is a very good school. think Non-factive implication Imagine/ consider/expect something/ reflect My secret is I think that about numbers in math as if they were money. feel Expressing emotional state/sensation/ impression of something Be aware of/ experience s.th physical or emotional/have the sensation/ sense You know, I feel better already. hate Expressing hatred feeling /expressing Strongly dislike/ be reluctant/ regret Man, I hate math! Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 57 Types Implicature Trigger Semantic mechanism Potential Implicature E.g. the critics’ emotion on something or someone A d je ct iv es big Showing metaphor Busy/important All right. Saturday's the big day. real Showing metaphor Actual /true A real challenge can occur. readable Showing metaphor Easily/enjoyably read/ understandable The essay is not organized yet, but it is readable. S et p h ra se s In a nut shell Giving conclusion Briefly/in summary/lastly Today, we'll talk about the most important things in management. In a nut shell, that means how to make things run smoothly. Without doubt Affirming/ asserting Certainly M: Is the lecture tonight worth attending? W: Without doubt. Not likely Doubting Certainly not M: Do you think Professor Simpson will cancel class on account of the special conference? W: Not likely. No way Under no circumstances or by no means (will something happen/be done) M: Do you think Mary will get there on time? W: No way. In te rj ec ti o n s Hey calling attention/ expressing surprise, joy etc. Used to call attention or express surprise or inquiry Hey, Tony. Want to go play basketball? Hmm expressing hesitation/ doubt or disagreement Used to express hesitation Hmm. When is the review session? oh expressing surprise/expressing pain/ expressing pleading Used for emphasis/to attract somebody’s attention Oh, that's great! What should I do now? Well expressing surprise/introducing a remark To express relief/ to resume a conversation or change the subject Well, let's look at what you need to do. 58 Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 4. Conclusion Although the use of linguistic units in the listening section of TOEFL iBT is various and abundant, this study reveals that seven categories of linguistic units (determiners, adverbs, linking words, adjectives, verbs, set phrases, and interjections) proposed by Gazdar (1979), Grice (1978), Levinson (1993), and Yule (1996) are commonly used in the listening section of TOEFL iBT. Noticeably, the most commonly used linguistic units are linking words, while the least commonly used ones are set phrases. Furthermore, since the use of linguistic units in utterances (lectures and conversations) in the listening section of TOEFL iBT is multifaceted, the implicatures of each category of linguistic units are accordingly diverse. This may possibly cause manifold difficulties for TOEFL iBT test-takers who are non-native speakers of English. Such findings, therefore, put forwards implications for the teaching of linguistic units and their implicatures in general and that of TOEFL iBT preparation in particular. First, the common categories and usages of linguistic units or devices (i.e., determiners, adverbs, linking words, adjectives, verbs, set phrases, and interjections) should be emphasized in helping to prepare EFL learners for TOEFL iBT test so that they are well aware of them. Specifically, examples of different types of linguistic units as well as sufficient practice should be given to learners in order that they are able to use them appropriately. Second, the teaching of implicatures should be explicitly taught in order to assist learners in understanding the underlying reasons of using implicature. In other words, TOEFL iBT test- takers should be offered with necessary guidance and theories of implicature interpretations so that they are fully aware of how implicature in different cases is interpreted. Apart from that, as the interpretation of implicature is deemed to evolve the knowledge of the target cultures, cultural knowledge should be embedded along with the teaching of implicature in order to enable learners to understand and interpret the implicatures appropriately and precisely. Thus, introducing background information in implicature interpretation to EFL learners is vital in assisting them to get familiar with cultural background knowledge. Finally, TOEFL iBT test-takers should be equipped with possible strategies and tips to understand and interpret the implicatures used in lectures and conversations of the listening section of TOEFL iBT References Edmun, P. & MacKinnon (2006). Developing Skills for the TOEFL® iBT (Intermediate). Los Angeles, CA: Compass Publishing. Educational Testing Service, (2007). The Official Guide to the TOEFL iBT .International Edition. Educational Testing Service (ETS) (2015). Test and Score Data Summary for TOEFL iBT Tests. International Edition. Gazdar, G. (1979). Pragmatics: Implicature, Presupposition, and Logic Form. New York: Academic. Green, G. M. (1996). Pragmatics and Natural Language Understanding. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Grice, P. (1978). Further Notes on Logic and Conversation. In P. Cole (Ed.), Syntax and Semantics: Vol.9, Pragmatics: 113-27. New York: Academic Press. Horn, L. R. (2004). Implicature. In L. R. Horn & W. Gregory (Eds.), The Handbook of Pragmatics, (pp. 3-28). Oxford: Blackwell. Jessop, H. L. (2009). TOEFL iBT Listening Breakthrough. Ho Chi Minh: Van Hoa Sai Gon Publishing house. Le T. N. Lien & Tran Q. Thao. Journal of Science Ho Chi Minh City Open University, 7(4), 47-59 59 Kate K. (2000). Implicature and Semantic Change. Retrieved from + and + Semantic +Change&oq=Implicature Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Link, W. Kushwaha, M. N., & Kato, M. (2007). How to Master Skills for the TOEFL iBT (Intermediate Listening). Ho Chi Minh: Nhan Tri Viet publishing house. MacGillivray, M., Yancey, P. & Malarcher C. (2006). Mastering Skills for the TOEFL® iBT: Advanced, 2006. Los Angeles, CA: Compass Publishing Mitchell S. G. (1998). Direct Reference and Implicature. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, 91(1), 61-90. Nguyen, G. T. (2000). Vietnamese Pragmatics (Dụng Học Việt Ngữ). Ha Noi: Publishing House of National University. Nguyen, N. H. T. (2007). An Investigation into Means to Signal Presuppositions and Implicatures in English Discourse. M.A. Thesis, Danang University. To, T. M. (2007). English Semantics. Ho Chi Minh City: The Publishing House of National University. Wierzbicka, A. (1992). The Semantics of Interjection. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 159-192. Worchester, A., Lark B., & Eric W. (2006). Building Skills for the TOEFL® iBT: Beginning. Los Angeles, CA: Compass Publishing. Yule, G. (1996). Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

File đính kèm:

the_use_of_linguistic_units_and_their_implicatures_in_the_li.pdf

the_use_of_linguistic_units_and_their_implicatures_in_the_li.pdf