Risk attitude and corporate investment under output market uncertainty: Evidence from the Me Kong river delta, Viet Nam

Investment is crucial to the development of

firms since it helps enhance product quality and

increase market share. Thus, good investment

decisions will raise firms’ efficiency and then

trigger economic growth (Maki et al., 2005).

However, making right investment decisions is

basically difficult, due to the output market uncertainty facing firm managers, among others

(e.g., competition and financing constraints).

As well perceived, investment decisions are

much dependent on firm managers’ risk attitude toward output market uncertainty (Bo and

Sterken, 2007; Femminis, 2008). Being skeptical about the loss that may result from poor investment decisions, risk-averse managers tend

to postpone investment intents so as to acquire

more relevant information. In this situation,

they possibly forgo good investment opportunities. On the other hand, risk-loving managers

who are normally over-optimistic about their

own competence and market prospect will proceed with investment opportunities, irrespective of their uncertain outcomes. This tendency

is accentuated by successes in the past. Such

over-optimistic behaviour may be problematic

if output markets would somehow turn worse.

Thus, investment decisions of both risk-averse

and risk-loving managers seem to have drawbacks that should be avoided.

The aim of this paper is to examine the impact of managers’ risk attitude on investment

by non-state firms in the Mekong River Delta (MRD) under output market uncertainty.

Findings of this paper will lay down a credible

ground for recommendations that enable firms

to make better investment decisions and proper long-term business strategies. This paper is

structured as follows. Section 1 introduces the

paper. Section 2 gives a review of the related

literature. Section 3 defines the empirical model out of the literature reviewed. Section 4 discusses the findings using a set of primary data

on 667 non-state firms in the MRD. Section 6

concludes the paper and renders recommendations.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Risk attitude and corporate investment under output market uncertainty: Evidence from the Me Kong river delta, Viet Nam

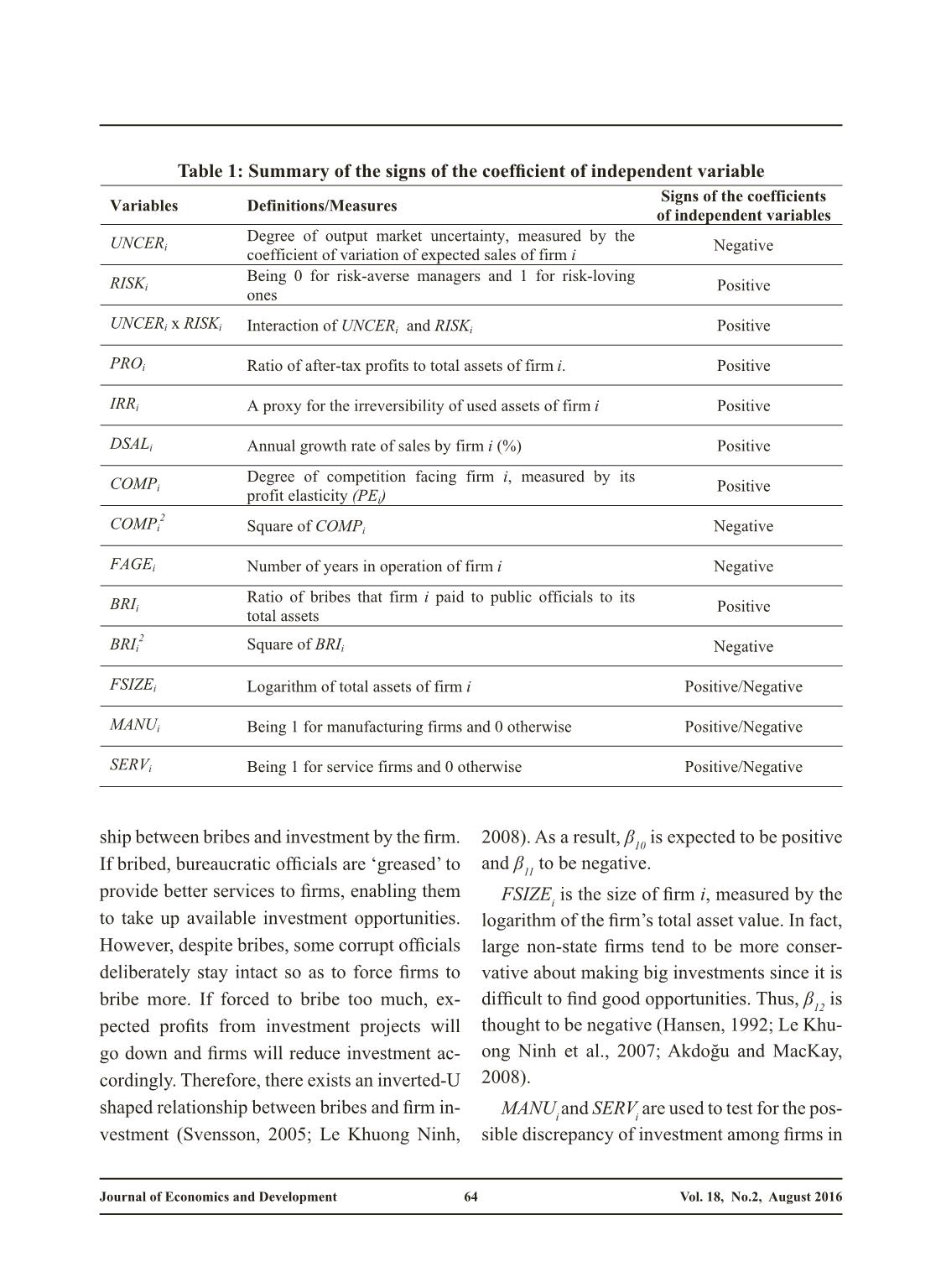

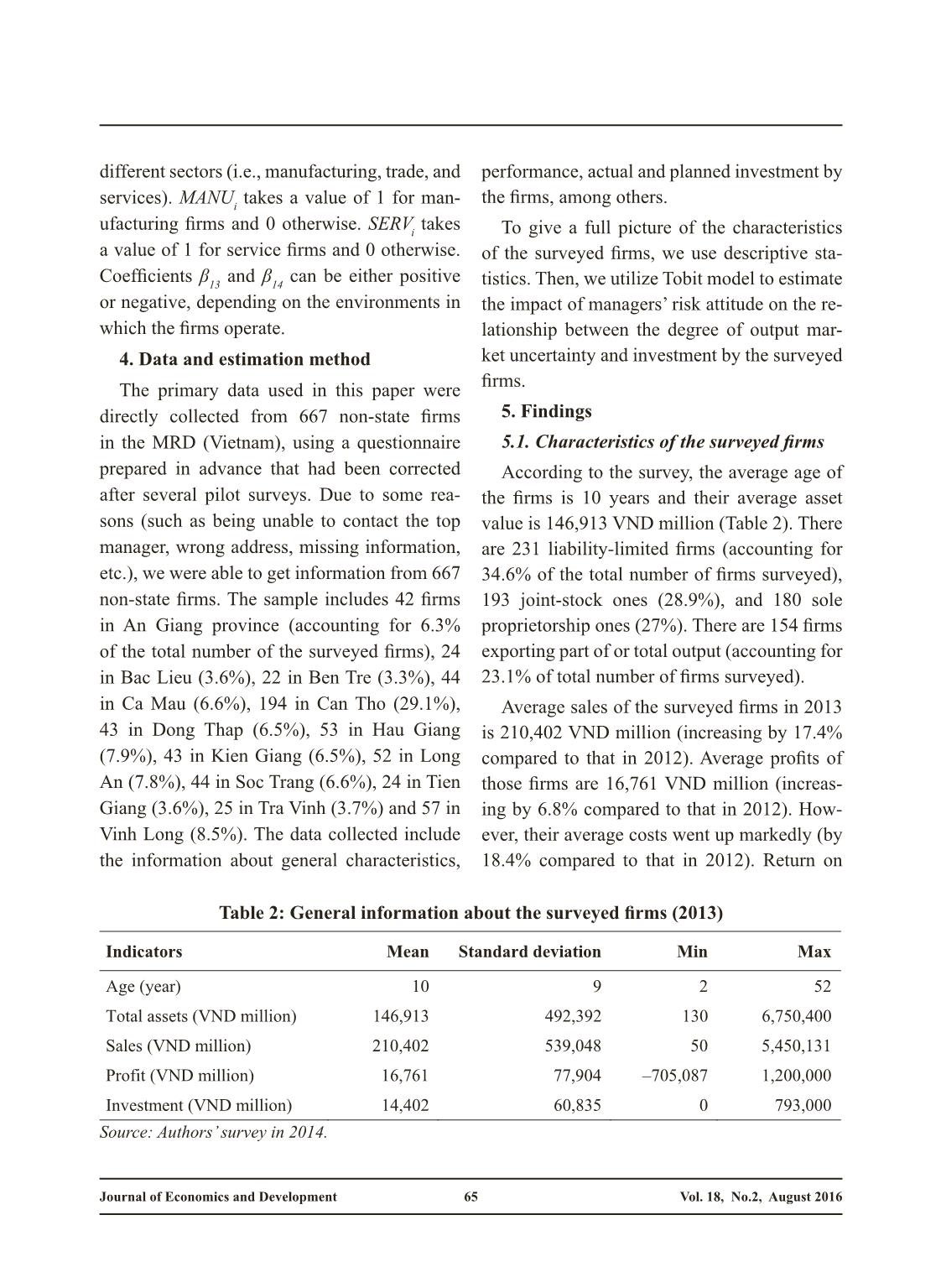

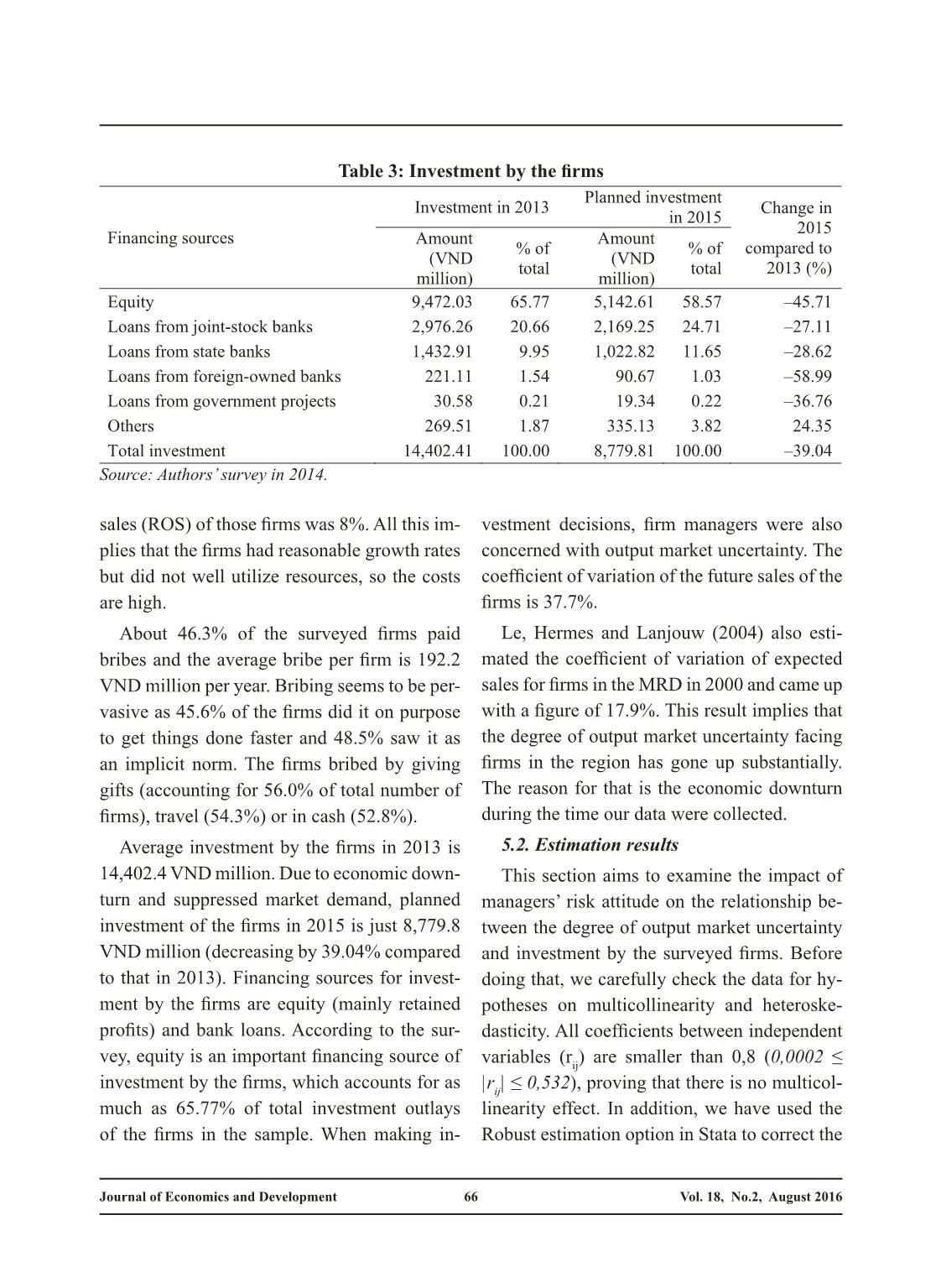

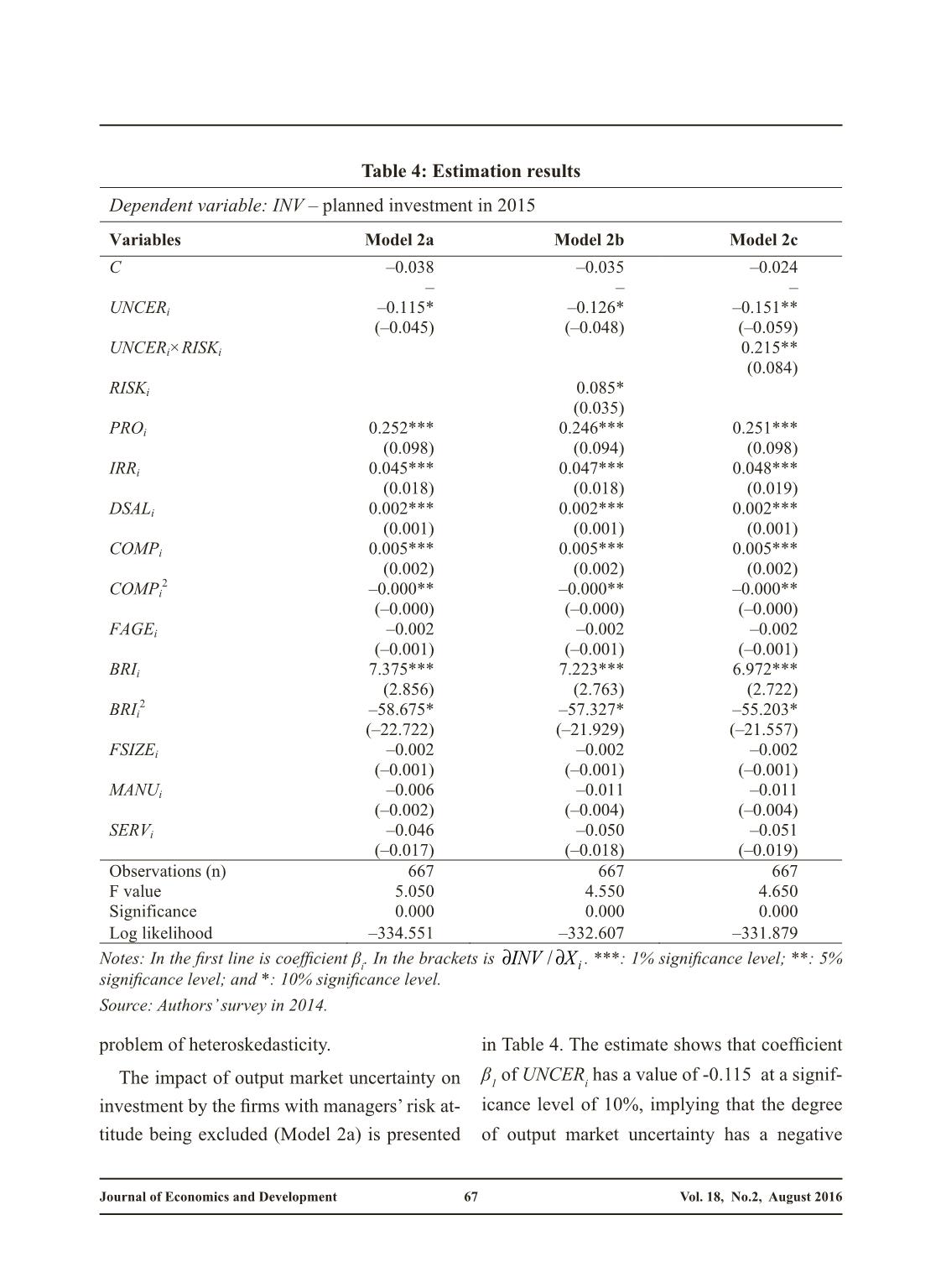

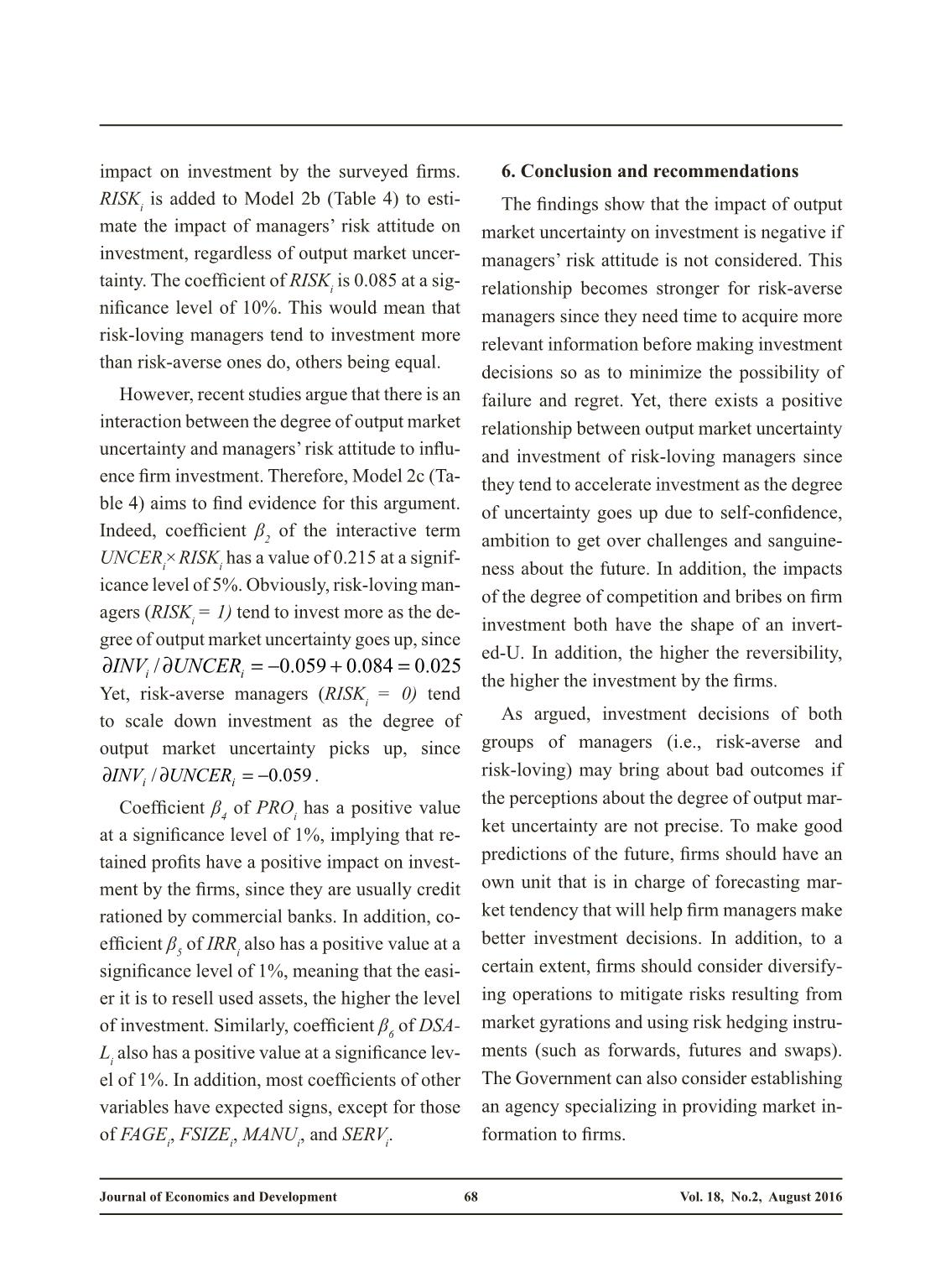

Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201659 Journal of Economics and Development, Vol.18, No.2, August 2016, pp. 59-70 ISSN 1859 0020 Risk Attitude and Corporate Investment under Output Market Uncertainty: Evidence from The Mekong River Delta, Vietnam Le Khuong Ninh Can Tho University, Vietnam Email: lekhuongninh@gmail.com Le Tan Nghiem Can Tho University, Vietnam Email: letannghiem@gmail.com Huynh Huu Tho Can Tho University, Vietnam Email: huynhhuuthoct@gmail.com Abstract This paper aims to detect the impact of firm managers’ risk attitude on the relationship between the degree of output market uncertainty and firm investment. The findings show that there is a negative relationship between these two aspects for risk-averse managers while there is a positive relationship for risk-loving ones, since they have different utility functions. Based on the findings, this paper proposes recommendations for firm managers to take into account when making investment decisions and long-term business strategies as well. Keywords: Competition; corruption; investment; market uncertainty; risk attitude. Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201660 1. Introduction Investment is crucial to the development of firms since it helps enhance product quality and increase market share. Thus, good investment decisions will raise firms’ efficiency and then trigger economic growth (Maki et al., 2005). However, making right investment decisions is basically difficult, due to the output market un- certainty facing firm managers, among others (e.g., competition and financing constraints). As well perceived, investment decisions are much dependent on firm managers’ risk atti- tude toward output market uncertainty (Bo and Sterken, 2007; Femminis, 2008). Being skepti- cal about the loss that may result from poor in- vestment decisions, risk-averse managers tend to postpone investment intents so as to acquire more relevant information. In this situation, they possibly forgo good investment opportu- nities. On the other hand, risk-loving managers who are normally over-optimistic about their own competence and market prospect will pro- ceed with investment opportunities, irrespec- tive of their uncertain outcomes. This tendency is accentuated by successes in the past. Such over-optimistic behaviour may be problematic if output markets would somehow turn worse. Thus, investment decisions of both risk-averse and risk-loving managers seem to have draw- backs that should be avoided. The aim of this paper is to examine the im- pact of managers’ risk attitude on investment by non-state firms in the Mekong River Del- ta (MRD) under output market uncertainty. Findings of this paper will lay down a credible ground for recommendations that enable firms to make better investment decisions and prop- er long-term business strategies. This paper is structured as follows. Section 1 introduces the paper. Section 2 gives a review of the related literature. Section 3 defines the empirical mod- el out of the literature reviewed. Section 4 dis- cusses the findings using a set of primary data on 667 non-state firms in the MRD. Section 6 concludes the paper and renders recommenda- tions. 2. Literature review When making investment decisions, firm managers do face output market uncertainty. To put it differently, they do not know the ex- act future sales. Thus, they tend to postpone investment in order to fetch more relevant in- formation and determine the right time to in- vest (Berk, 1999). According to Nishihara and Shibata (2014), unless firms have to invest to preempt competitors, most investment projects can be postponed, since for most of the time, investment opportunities remain for a certain period prior to absolutely expiring. Indeed, having an investment opportunity (a real op- tion) is analogous to owning a European call option to buy a stock. Then, the owner can ex- ercise it right away, or later, to get a financial asset with a certain value (e.g., a stock). When possessing a real option (i.e., an investment op- portunity), the firm can decide to invest right away or at any future point of time to obtain a real asset with a certain value (e.g., a facto- ry). Like call options, the value of real options stems from the managerial flexibility in making use of the uncertainty about the future value of the real asset (Luehrman, 1998). Due to uncer- tainty, firm managers tend to wait for more in- formation that helps to avoid failure. Thus, researchers have tried to examine the impact of output market uncertainty on firm Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201661 investment. Most of the empirical studies on this topic (Guiso and Parigi, 1999; Ghosal and Loungani, 2000; Le, Hermes and Lanjouw, 2004) came up with evidence of negative rel ... cteristics of the surveyed firms According to the survey, the average age of the firms is 10 years and their average asset value is 146,913 VND million (Table 2). There are 231 liability-limited firms (accounting for 34.6% of the total number of firms surveyed), 193 joint-stock ones (28.9%), and 180 sole proprietorship ones (27%). There are 154 firms exporting part of or total output (accounting for 23.1% of total number of firms surveyed). Average sales of the surveyed firms in 2013 is 210,402 VND million (increasing by 17.4% compared to that in 2012). Average profits of those firms are 16,761 VND million (increas- ing by 6.8% compared to that in 2012). How- ever, their average costs went up markedly (by 18.4% compared to that in 2012). Return on Table 2: General information about the surveyed firms (2013) Source: Authors’ survey in 2014. Indicators Mean Standard deviation Min Max Age (year) 10 9 2 52 Total assets (VND million) 146,913 492,392 130 6,750,400 Sales (VND million) 210,402 539,048 50 5,450,131 Profit (VND million) 16,761 77,904 –705,087 1,200,000 Investment (VND million) 14,402 60,835 0 793,000 Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201666 sales (ROS) of those firms was 8%. All this im- plies that the firms had reasonable growth rates but did not well utilize resources, so the costs are high. About 46.3% of the surveyed firms paid bribes and the average bribe per firm is 192.2 VND million per year. Bribing seems to be per- vasive as 45.6% of the firms did it on purpose to get things done faster and 48.5% saw it as an implicit norm. The firms bribed by giving gifts (accounting for 56.0% of total number of firms), travel (54.3%) or in cash (52.8%). Average investment by the firms in 2013 is 14,402.4 VND million. Due to economic down- turn and suppressed market demand, planned investment of the firms in 2015 is just 8,779.8 VND million (decreasing by 39.04% compared to that in 2013). Financing sources for invest- ment by the firms are equity (mainly retained profits) and bank loans. According to the sur- vey, equity is an important financing source of investment by the firms, which accounts for as much as 65.77% of total investment outlays of the firms in the sample. When making in- vestment decisions, firm managers were also concerned with output market uncertainty. The coefficient of variation of the future sales of the firms is 37.7%. Le, Hermes and Lanjouw (2004) also esti- mated the coefficient of variation of expected sales for firms in the MRD in 2000 and came up with a figure of 17.9%. This result implies that the degree of output market uncertainty facing firms in the region has gone up substantially. The reason for that is the economic downturn during the time our data were collected. 5.2. Estimation results This section aims to examine the impact of managers’ risk attitude on the relationship be- tween the degree of output market uncertainty and investment by the surveyed firms. Before doing that, we carefully check the data for hy- potheses on multicollinearity and heteroske- dasticity. All coefficients between independent variables (rij) are smaller than 0,8 (0,0002 ≤ |rij| ≤ 0,532), proving that there is no multicol- linearity effect. In addition, we have used the Robust estimation option in Stata to correct the Table 3: Investment by the firms Source: Authors’ survey in 2014. Financing sources Investment in 2013 Planned investment in 2015 Change in 2015 compared to 2013 (%) Amount (VND million) % of total Amount (VND million) % of total Equity 9,472.03 65.77 5,142.61 58.57 –45.71 Loans from joint-stock banks 2,976.26 20.66 2,169.25 24.71 –27.11 Loans from state banks 1,432.91 9.95 1,022.82 11.65 –28.62 Loans from foreign-owned banks 221.11 1.54 90.67 1.03 –58.99 Loans from government projects 30.58 0.21 19.34 0.22 –36.76 Others 269.51 1.87 335.13 3.82 24.35 Total investment 14,402.41 100.00 8,779.81 100.00 –39.04 Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201667 Table 4: Estimation results Notes: In the first line is coefficient βi. In the brackets is iXINV ∂∂ / . ***: 1% significance level; **: 5% significance level; and *: 10% significance level. Source: Authors’ survey in 2014. Dependent variable: INV – planned investment in 2015 Variables Model 2a Model 2b Model 2c C –0.038 – –0.035 – –0.024 – UNCERi –0.115* (–0.045) –0.126* (–0.048) –0.151** (–0.059) UNCERi×RISKi 0.215** (0.084) RISKi 0.085* (0.035) PROi 0.252*** (0.098) 0.246*** (0.094) 0.251*** (0.098) IRRi 0.045*** (0.018) 0.047*** (0.018) 0.048*** (0.019) DSALi 0.002*** (0.001) 0.002*** (0.001) 0.002*** (0.001) COMPi 0.005*** (0.002) 0.005*** (0.002) 0.005*** (0.002) COMPi2 –0.000** (–0.000) –0.000** (–0.000) –0.000** (–0.000) FAGEi –0.002 (–0.001) –0.002 (–0.001) –0.002 (–0.001) BRIi 7.375*** (2.856) 7.223*** (2.763) 6.972*** (2.722) BRIi 2 –58.675* (–22.722) –57.327* (–21.929) –55.203* (–21.557) FSIZEi –0.002 (–0.001) –0.002 (–0.001) –0.002 (–0.001) MANUi –0.006 (–0.002) –0.011 (–0.004) –0.011 (–0.004) SERVi –0.046 (–0.017) –0.050 (–0.018) –0.051 (–0.019) Observations (n) 667 667 667 F value 5.050 4.550 4.650 Significance 0.000 0.000 0.000 Log likelihood –334.551 –332.607 –331.879 problem of heteroskedasticity. The impact of output market uncertainty on investment by the firms with managers’ risk at- titude being excluded (Model 2a) is presented in Table 4. The estimate shows that coefficient β1 of UNCERi has a value of -0.115 at a signif- icance level of 10%, implying that the degree of output market uncertainty has a negative Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201668 impact on investment by the surveyed firms. RISKi is added to Model 2b (Table 4) to esti- mate the impact of managers’ risk attitude on investment, regardless of output market uncer- tainty. The coefficient of RISKi is 0.085 at a sig- nificance level of 10%. This would mean that risk-loving managers tend to investment more than risk-averse ones do, others being equal. However, recent studies argue that there is an interaction between the degree of output market uncertainty and managers’ risk attitude to influ- ence firm investment. Therefore, Model 2c (Ta- ble 4) aims to find evidence for this argument. Indeed, coefficient β2 of the interactive term UNCERi×RISKi has a value of 0.215 at a signif- icance level of 5%. Obviously, risk-loving man- agers (RISKi = 1) tend to invest more as the de- gree of output market uncertainty goes up, since 025.0084.0059.0/ =+−=∂∂ ii UNCERINV Yet, risk-averse managers (RISKi = 0) tend to scale down investment as the degree of output market uncertainty picks up, since 059.0/ −=∂∂ ii UNCERINV . Coefficient β4 of PROi has a positive value at a significance level of 1%, implying that re- tained profits have a positive impact on invest- ment by the firms, since they are usually credit rationed by commercial banks. In addition, co- efficient β5 of IRRi also has a positive value at a significance level of 1%, meaning that the easi- er it is to resell used assets, the higher the level of investment. Similarly, coefficient β6 of DSA- Li also has a positive value at a significance lev- el of 1%. In addition, most coefficients of other variables have expected signs, except for those of FAGEi, FSIZEi, MANUi, and SERVi. 6. Conclusion and recommendations The findings show that the impact of output market uncertainty on investment is negative if managers’ risk attitude is not considered. This relationship becomes stronger for risk-averse managers since they need time to acquire more relevant information before making investment decisions so as to minimize the possibility of failure and regret. Yet, there exists a positive relationship between output market uncertainty and investment of risk-loving managers since they tend to accelerate investment as the degree of uncertainty goes up due to self-confidence, ambition to get over challenges and sanguine- ness about the future. In addition, the impacts of the degree of competition and bribes on firm investment both have the shape of an invert- ed-U. In addition, the higher the reversibility, the higher the investment by the firms. As argued, investment decisions of both groups of managers (i.e., risk-averse and risk-loving) may bring about bad outcomes if the perceptions about the degree of output mar- ket uncertainty are not precise. To make good predictions of the future, firms should have an own unit that is in charge of forecasting mar- ket tendency that will help firm managers make better investment decisions. In addition, to a certain extent, firms should consider diversify- ing operations to mitigate risks resulting from market gyrations and using risk hedging instru- ments (such as forwards, futures and swaps). The Government can also consider establishing an agency specializing in providing market in- formation to firms. Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201669 Notes: 1. From the data gathered, we are able to calculate the conditional mean and variance of the growth rate of sales in 2015 as perceived in 2014 ( 0S is the sales in the base year (2013), ed is the expected mean of the growth of sales in 2015 and e)( 2σ is the expected variance of the growth rate of sales in 2015). Based on those variables, we calculate the coefficient of variation of expected sales . References Aghion, P., Bloom, N., Blundell, R., Griffith, R. and Howitt, P. (2005), ‘Competition and Innovation: An Inverted–U Relationship’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(2), 701–728. Aistov, A. and Kuzmicheva, E. (2012), ‘Investment Decisions under Uncertainty: Example of Russian Companies’, Proceedings in Finance and Risk Perspectives, 12, 378–392. Akdoğu, E. and MacKay, P. (2008), ‘Investment and Competition’, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 43(2), 299–330. Andrade, G. and Stafford, E. (2004), ‘Investigating the Economic Role of Mergers’, Journal of Corporate Finance, 10, 1–36. Antonides, G. and Van der Sar, N. L. (1990), ‘Individual Expectations, Risk Perception and Preferences in Relation to Investment Decision Making’, Journal of Economic Psychology, 11, 227-245. Bayraktar, N. (2014), ‘Fixed Investment/Fundamental Sensitivities under Financial Constraints’, Journal of Economics and Business, 75, 25–59. Berk, J. (1999), ‘A Simple Approach for Deciding When to Invest’, American Economic Review 89(5), 1319–1326. Block, J., Sandner, P. and Spiegel (2015), ‘How Do Risk Attitudes Differ within the Group of Entrepreneurs? The Role of Motivation and Procedural Utility’, Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 183– 206. Bo, H. and Lensink, R. (2005), ‘Is the Investment–Uncertainty Relationship Non-Linear? An Empirical Analysis for the Netherlands,’ Economica, 72(286), 307–331. Bo, H. and Sterken, S. (2007), ‘Attitude towards Risk, Uncertainty, and Fixed Investment,’ The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 18(1), 59–75. Boone, J. (2000), ‘Competitive Pressure: the Effects on Investments in Product and Process Innovation’, Rand Journal of Economics, 31(3), 549–569. Boone, J. (2001), ‘Intensity of Competition and the Incentive to Innovate’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 19, 705–726. Boone, J. (2008), ‘A New Way to Measure Competition’, Economic Journal, 118, 1245–1261. Chronopoulos, M., De Reyck, B. and Siddiqui, A. (2011), ‘Optimal Investment under Operational Flexibility, Risk Aversion, and Uncertainty’, European Journal of Operational Research, 213, 221–237. Driver, C. and Whelan, B. (2001), ‘The Effect of Business Risk on Manufacturing Investment Sectorial Survey Evidence from Ireland’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 44, 403–412. Femminis, G. (2008), ‘Risk-Aversion and the Investment–Uncertainty Relationship: The Role of Capital Depreciation’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65, 585–591. Ghosal, V. and Loungani, P. (2000), ‘The Differential Impact of Uncertainty on Investment in Small and Large Businesses’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(2), 338-343. Journal of Economics and Development Vol. 18, No.2, August 201670 Guiso, L. and Parigi, G. (1999), ‘Investment and Demand Uncertainty’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 185–227. Hansen, J. A. (1992), ‘Innovation, Firm Size, and Firm Age’, Small Business Economics, 4(1), 37-44. Le Khuong Ninh (2008), ‘Bribing and Investment Decisions by Non-state Firms in the Mekong River Delta’, Economic Review, 3-2008 (in Vietnamese), 68–76. Le Khuong Ninh, Hermes, N. and Lanjouw, G. (2004), ‘Investment, Uncertainty and Irreversibility: An Empirical Study of Rice Mills in the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam’, Economics of Transition 12(2), 307–332. Le Khuong Ninh, Phan Anh Tu, Pham Le Thong, Le Tan Nghiem and Huynh Viet Khai (2007), ‘An Analysis of Factors Affecting Investment Decisions by Non-state Firms in the Mekong River Delta’, Economic Review, 4-2007 (in Vietnamese), 47–55. Luehrman, T., (1998), ‘Investment Opportunities as Real Options: Getting Started on the Numbers’, Harvard Business Review, July-August, 3–15. Maki, T., Yotsuya, K. and Yagi, T. (2005), ‘Economic Growth and the Riskiness of Investment in Firm- Specific Skills’, European Economic Review, 49, 1033–1049. Moohammad, A. Y., Nor’Aini, Y., and Kamal, E. M. (2014), ‘Influences of Firm Size, Age and Sector on Innovation Behavior of Construction Consultancy Services Organizations in Developing Countries’, Culture, 4(4), 01-09. Moretto, M. (2008), ‘Competition and Irreversible Investments under Uncertainty’, Information Economics and Policy, 20, 75–88. Nakamura, T. (1999), ‘Risk-Aversion and the Uncertainty-Investment Relationship: A Note’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 38, 357–363. Nielsen, M.J. (2002), ‘Competition and Irreversible Investments’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20(2002), 731–743. Nishihara, M. and Shibata, T. (2014), ‘Preemption, Leverage, and Financing Constraints’, Review of Financial Economics, 23, 75–89. Polder, M and Veldhuizen, E. (2012), ‘Innovation and Competition in the Netherlands: Testing the Inverted–U for Industries and Firms’, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 12(1), 67–91. Svensson, J. (2005), ‘Eight Questions about Corruption’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(3), 19–42. Whalley, A. E. (2011), ‘Optimal R&D Investment for a Risk-Averse Entrepreneur’, Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, 35, 413–429.

File đính kèm:

risk_attitude_and_corporate_investment_under_output_market_u.pdf

risk_attitude_and_corporate_investment_under_output_market_u.pdf