Constructivism and cooperative learning: An application in teaching interpreting to senior students of business english at the university of finance – marketing

Abstract: The paper discusses the application of constructivism to teaching interpreting to senior

students of Business English at the University of Finance-Marketing’s Foreign Language Department.

In fact, the author depicts the classroom model, in which the constructivist approach in combination

with cooperative learning is adopted in two empirical courses. The participant observation and

questionnaire reveal that the students are really interested in and inspired by the constructivist approach

to teaching interpreting at tertiary level, and the factor analysis of material preference, language

proficiency, confidence, methods and the teacher through data statistics indicates that the students like

and support the empirical courses, and the teacher is the most influential on students’ learning and the

most satisfying factor.

Key words: Constructivism, cooperative learning, cognitive development, language proficiency

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Constructivism and cooperative learning: An application in teaching interpreting to senior students of business english at the university of finance – marketing

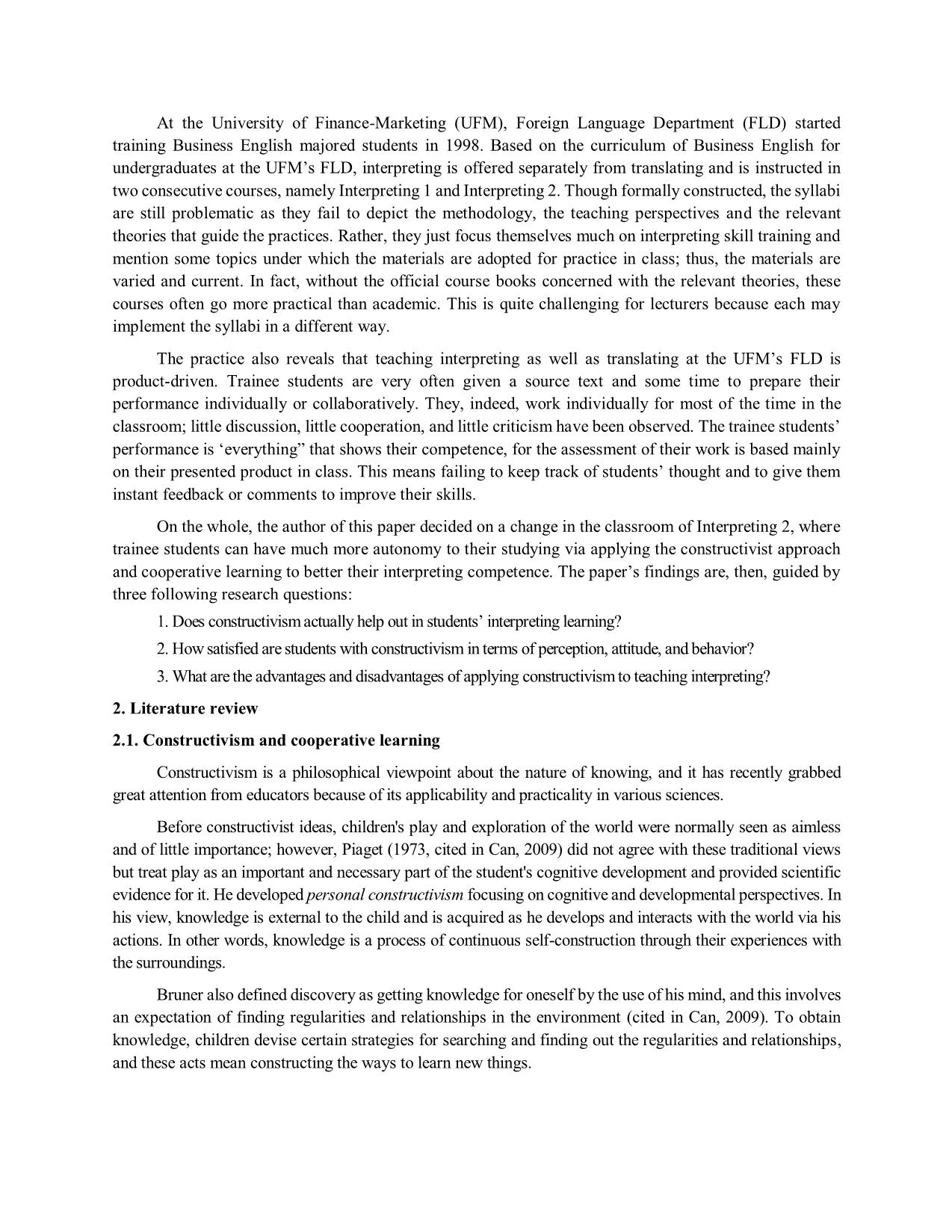

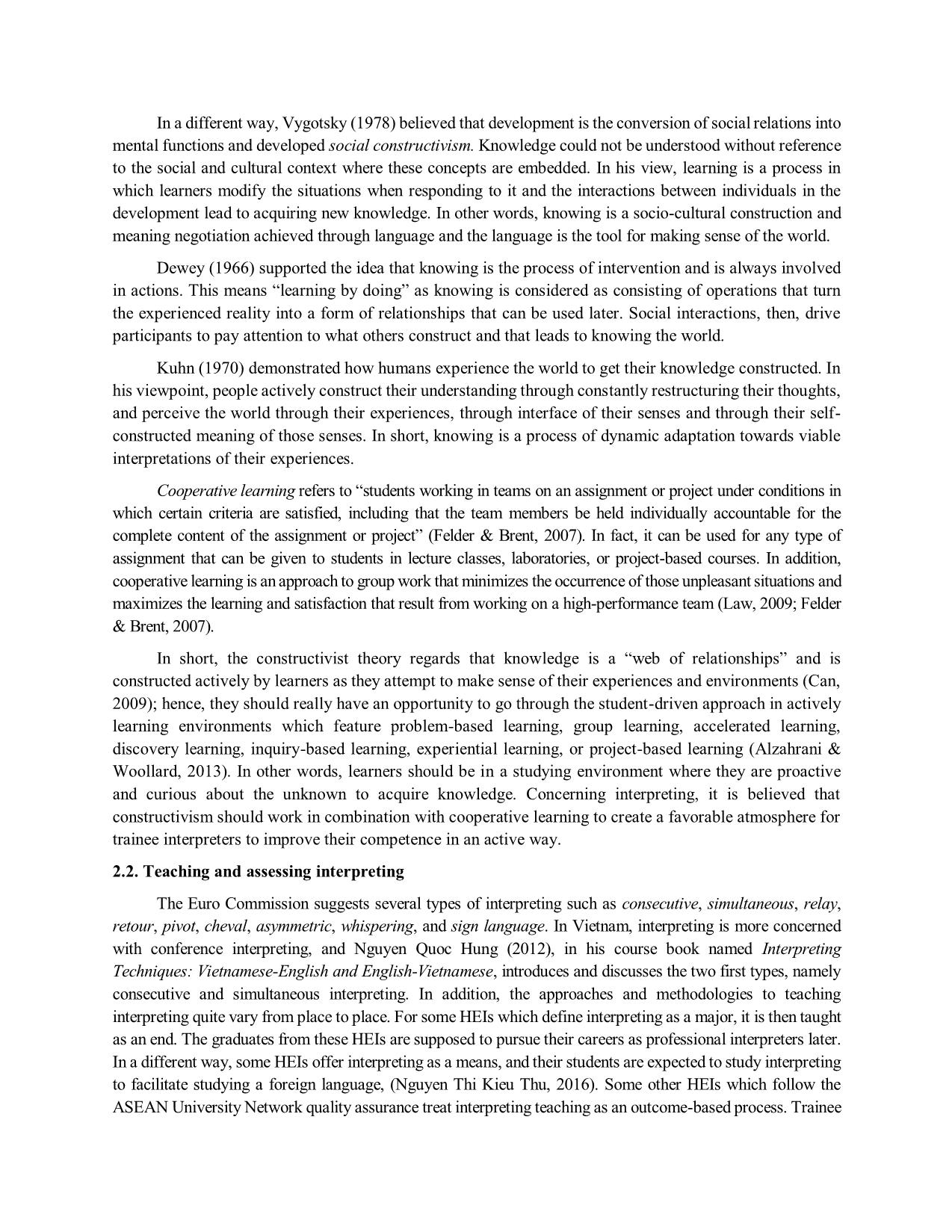

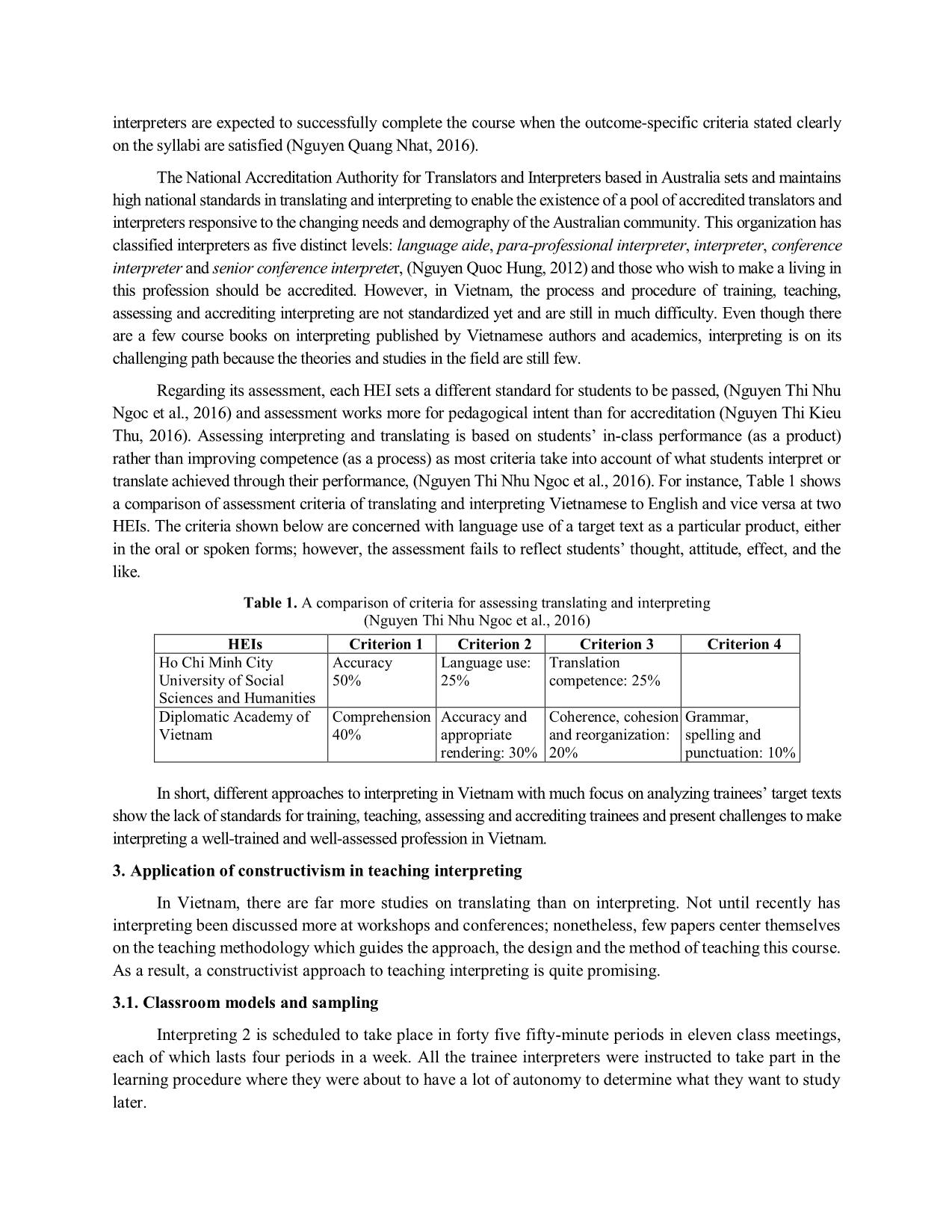

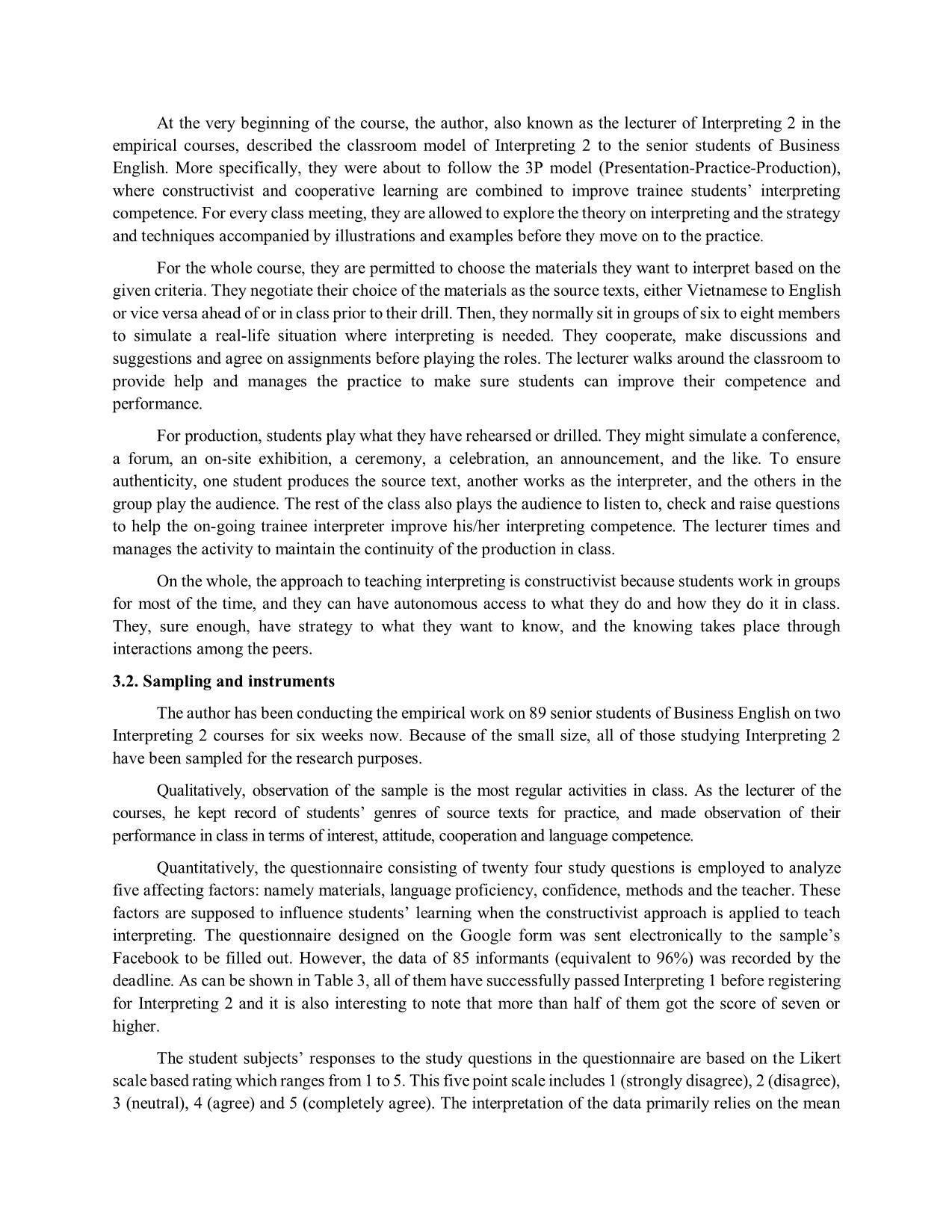

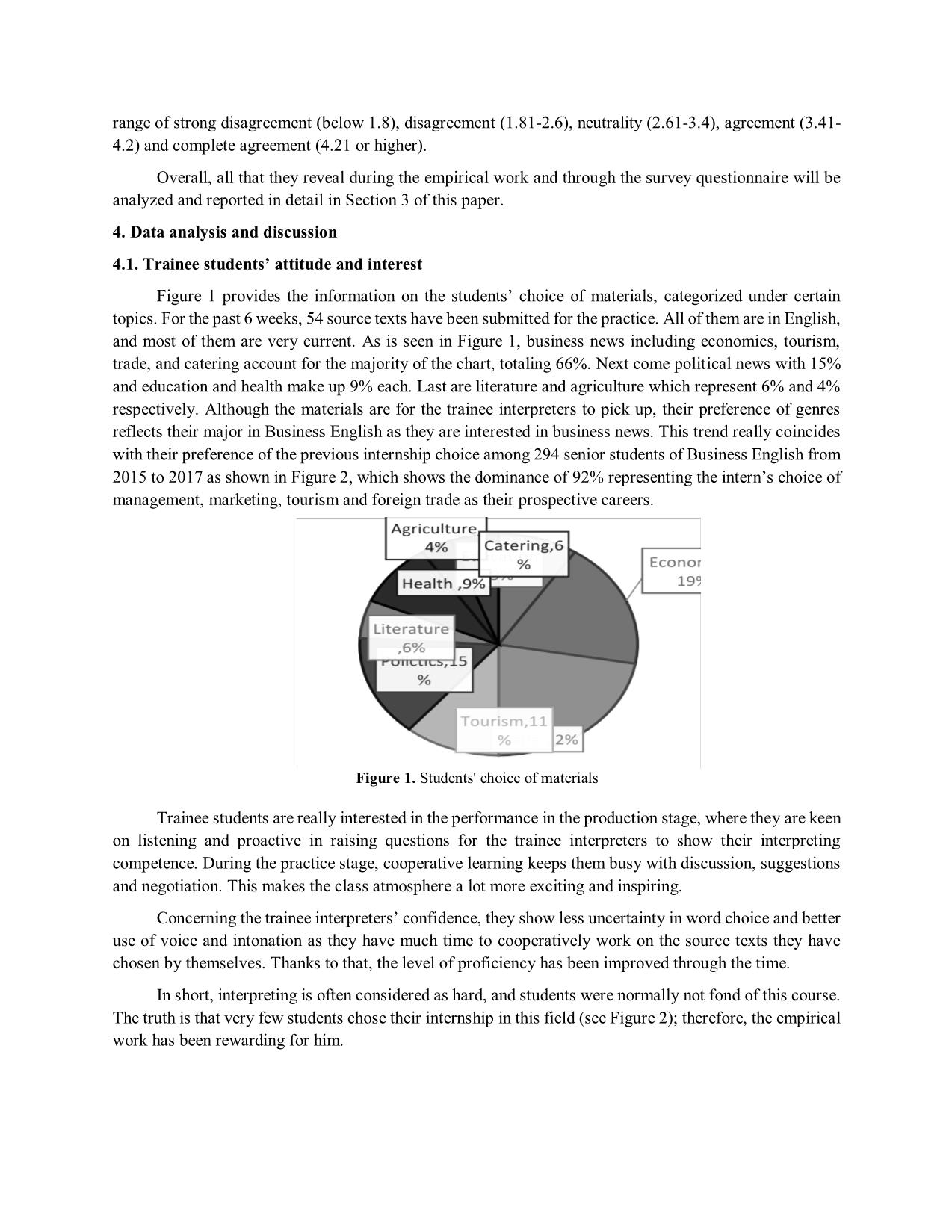

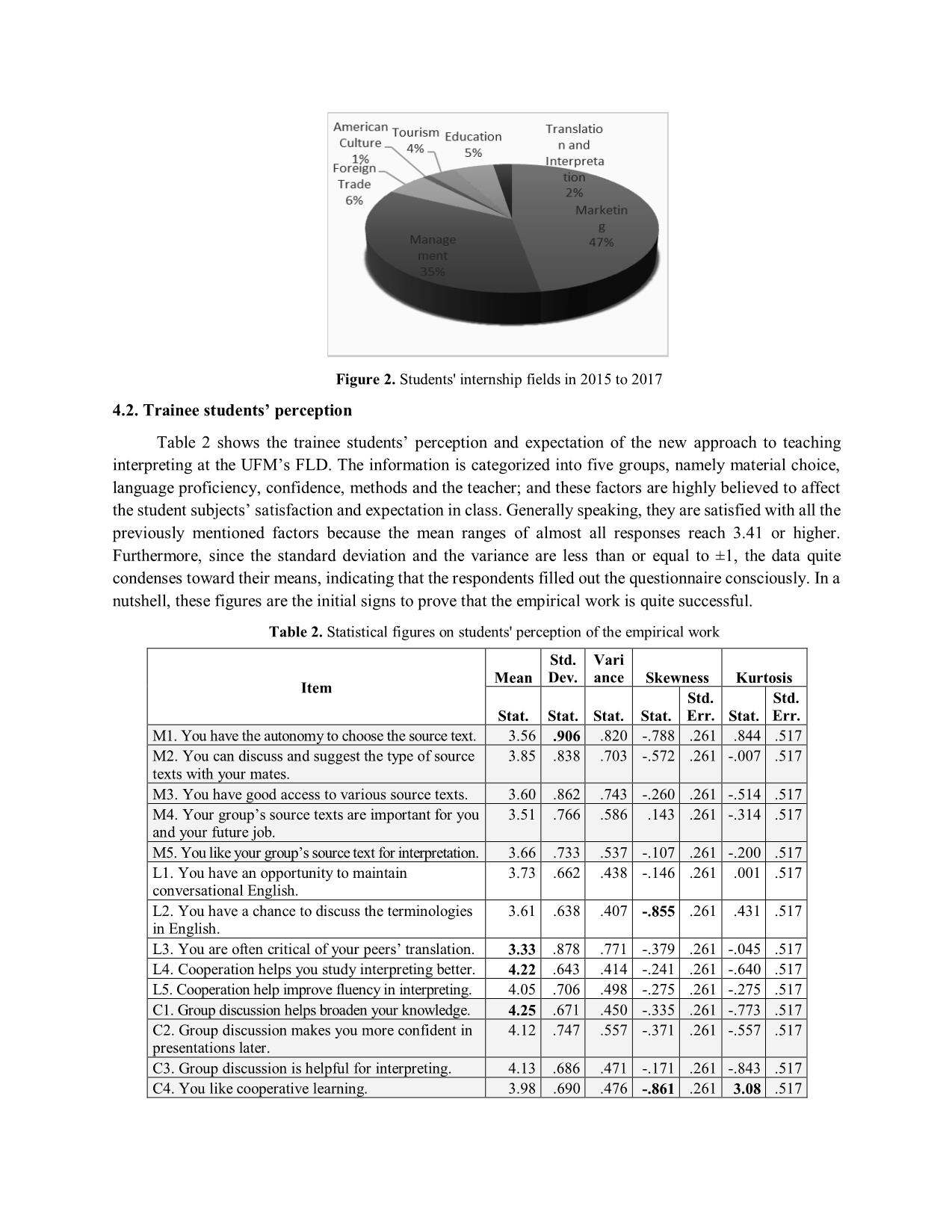

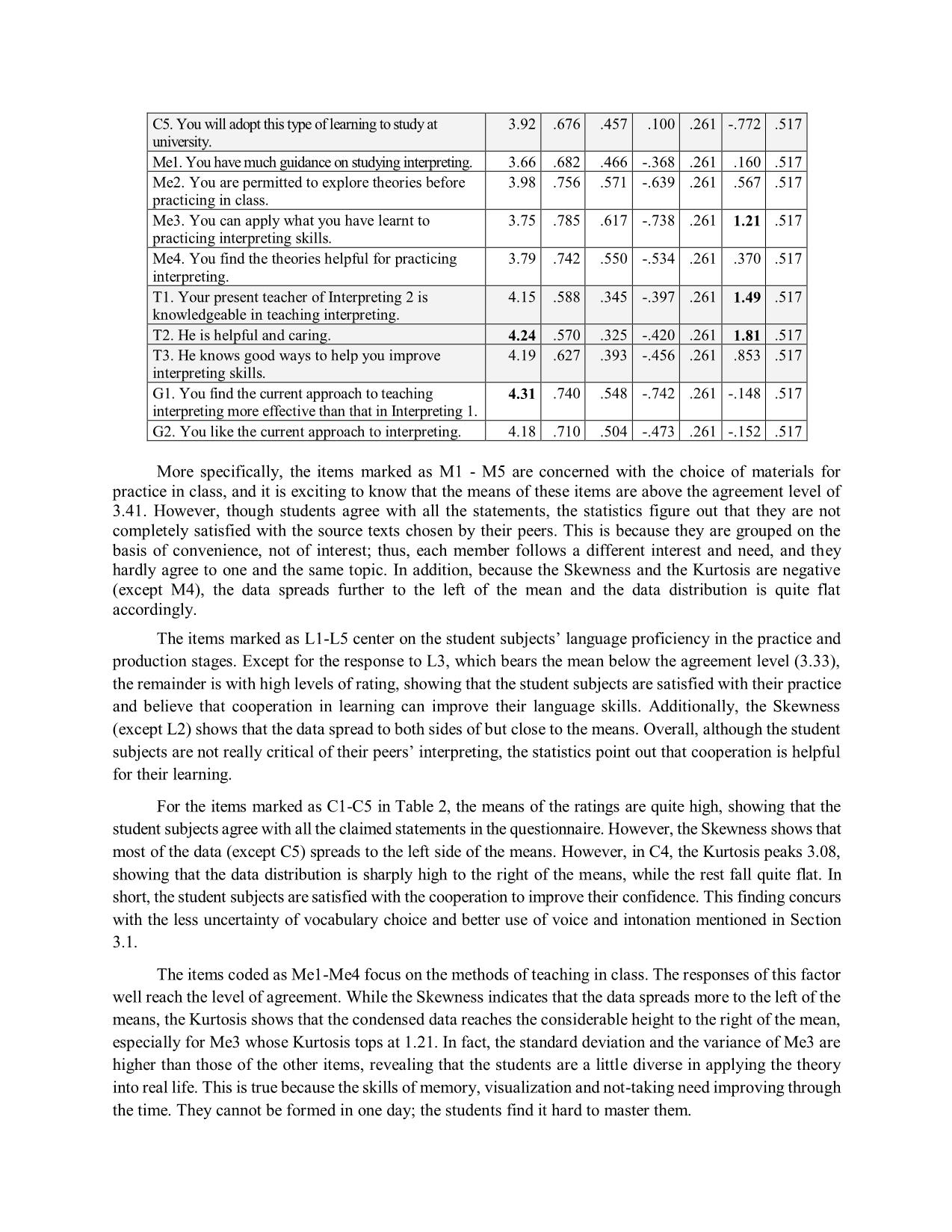

CONSTRUCTIVISM AND COOPERATIVE LEARNING: AN APPLICATION IN TEACHING INTERPRETING TO SENIOR STUDENTS OF BUSINESS ENGLISH AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FINANCE–MARKETING Chu Quang Phe * University of Finance-Marketing Received: 27/06/2017; Revised: 20/07/2017; Accepted: 30/08/2018 Abstract: The paper discusses the application of constructivism to teaching interpreting to senior students of Business English at the University of Finance-Marketing’s Foreign Language Department. In fact, the author depicts the classroom model, in which the constructivist approach in combination with cooperative learning is adopted in two empirical courses. The participant observation and questionnaire reveal that the students are really interested in and inspired by the constructivist approach to teaching interpreting at tertiary level, and the factor analysis of material preference, language proficiency, confidence, methods and the teacher through data statistics indicates that the students like and support the empirical courses, and the teacher is the most influential on students’ learning and the most satisfying factor. Key words: Constructivism, cooperative learning, cognitive development, language proficiency 1. Introduction Translation is “rendering the meaning of a text into another language in the way that the author intended the text” (Newmark, 1988, p. 5), and there would be no global communication without it (Newmark, 2003, cited in Nguyen Thi Nhu Ngoc, Nguyen Thi Kieu Thu & Le Thi Ngoc Anh, 2016). Since Vietnam’s open-door policy, there has been a mounting demand for translating and interpreting due largely to its increasing economic, diplomatic and commercial relations with other countries. Then, translating and interpreting, which play a part in foreign language teaching and learning, especially at universities, colleges, academies and institutes (higher education institutions or HEIs), where students study to earn a degree in linguistics or applied linguistics, become more and more popular on the employment market and have been pursued by many as their life-long careers after graduation. Currently, about sixty HEIs are training translating and interpreting, either as a discipline or as a major, and the importance and popularity of this profession actually led to the official establishment of Vietnam Translator and Interpreter Group in 2015, in a hope to improve expertise and business in the field, and help increase training, teaching, assessing and accrediting trainees in the future (Nguyen Thi Nhu Ngoc et al., 2016). Interpreting is “to translate one language into another as you hear it”, (Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary) or “oral translation” (Nguyen Thi Kieu Thu, 2016). This skill has long been taught in Vietnam either in combination with or in separation from translating; nonetheless, it has gained much attention for two decades now at HEIs which teach foreign languages with the foundation of faculty departments of translating and interpreting (Nguyen Thi Kieu Thu, 2016). Although there have been numerous forums, workshops, and conferences, either online or offline on interpreting, researchers and lecturers still find it hard to spot the best approaches and methodologies on teaching, training, and assessing interpreting in Vietnam. * Email: cq.phe@ufm.edu.vn At the University of Finance-Marketing (UFM), Foreign Language Department (FLD) started training Business English majored students in 1998. Based on the curriculum of Business English for undergraduates at the UFM’s FLD, interpreting is offered separately from translating and is instructed in two consecutive courses, namely Interpreting 1 and Interpreting 2. Though formally constructed, the syllabi are still problematic as they fail to depict the methodology, the teaching perspectives and the relevant theories that guide the practices. Rather, they just focus themselves much on interpreting skill training and mention some topics under which the materials are adopted for practice in class; thus, the materials are varied and current. In fact, without the official course books concerned with the relevant theories, these courses often go more practical than academic. This is quite challenging for lecturers because each may implement the syllabi in a different way. The practice also reveals that teaching interpreting as well as translating at the UFM’s FLD is product-driven. Trainee students are very often given a source text and some time to prepare their performance individually or collaboratively. They, indeed, work individually for most of the time in the classroom; little discussion, little cooperation, and little criticism have been observed. The trainee students’ performance is ‘everything” that shows their competence, for the assessment of their work is based mainly on their presented product in class. This means failing to keep track of students’ thou ... all that they reveal during the empirical work and through the survey questionnaire will be analyzed and reported in detail in Section 3 of this paper. 4. Data analysis and discussion 4.1. Trainee students’ attitude and interest Figure 1 provides the information on the students’ choice of materials, categorized under certain topics. For the past 6 weeks, 54 source texts have been submitted for the practice. All of them are in English, and most of them are very current. As is seen in Figure 1, business news including economics, tourism, trade, and catering account for the majority of the chart, totaling 66%. Next come political news with 15% and education and health make up 9% each. Last are literature and agriculture which represent 6% and 4% respectively. Although the materials are for the trainee interpreters to pick up, their preference of genres reflects their major in Business English as they are interested in business news. This trend really coincides with their preference of the previous internship choice among 294 senior students of Business English from 2015 to 2017 as shown in Figure 2, which shows the dominance of 92% representing the intern’s choice of management, marketing, tourism and foreign trade as their prospective careers. Figure 1. Students' choice of materials Trainee students are really interested in the performance in the production stage, where they are keen on listening and proactive in raising questions for the trainee interpreters to show their interpreting competence. During the practice stage, cooperative learning keeps them busy with discussion, suggestions and negotiation. This makes the class atmosphere a lot more exciting and inspiring. Concerning the trainee interpreters’ confidence, they show less uncertainty in word choice and better use of voice and intonation as they have much time to cooperatively work on the source texts they have chosen by themselves. Thanks to that, the level of proficiency has been improved through the time. In short, interpreting is often considered as hard, and students were normally not fond of this course. The truth is that very few students chose their internship in this field (see Figure 2); therefore, the empirical work has been rewarding for him. Figure 2. Students' internship fields in 2015 to 2017 4.2. Trainee students’ perception Table 2 shows the trainee students’ perception and expectation of the new approach to teaching interpreting at the UFM’s FLD. The information is categorized into five groups, namely material choice, language proficiency, confidence, methods and the teacher; and these factors are highly believed to affect the student subjects’ satisfaction and expectation in class. Generally speaking, they are satisfied with all the previously mentioned factors because the mean ranges of almost all responses reach 3.41 or higher. Furthermore, since the standard deviation and the variance are less than or equal to ±1, the data quite condenses toward their means, indicating that the respondents filled out the questionnaire consciously. In a nutshell, these figures are the initial signs to prove that the empirical work is quite successful. Table 2. Statistical figures on students' perception of the empirical work Item Mean Std. Dev. Vari ance Skewness Kurtosis Stat. Stat. Stat. Stat. Std. Err. Stat. Std. Err. M1. You have the autonomy to choose the source text. 3.56 .906 .820 -.788 .261 .844 .517 M2. You can discuss and suggest the type of source texts with your mates. 3.85 .838 .703 -.572 .261 -.007 .517 M3. You have good access to various source texts. 3.60 .862 .743 -.260 .261 -.514 .517 M4. Your group’s source texts are important for you and your future job. 3.51 .766 .586 .143 .261 -.314 .517 M5. You like your group’s source text for interpretation. 3.66 .733 .537 -.107 .261 -.200 .517 L1. You have an opportunity to maintain conversational English. 3.73 .662 .438 -.146 .261 .001 .517 L2. You have a chance to discuss the terminologies in English. 3.61 .638 .407 -.855 .261 .431 .517 L3. You are often critical of your peers’ translation. 3.33 .878 .771 -.379 .261 -.045 .517 L4. Cooperation helps you study interpreting better. 4.22 .643 .414 -.241 .261 -.640 .517 L5. Cooperation help improve fluency in interpreting. 4.05 .706 .498 -.275 .261 -.275 .517 C1. Group discussion helps broaden your knowledge. 4.25 .671 .450 -.335 .261 -.773 .517 C2. Group discussion makes you more confident in presentations later. 4.12 .747 .557 -.371 .261 -.557 .517 C3. Group discussion is helpful for interpreting. 4.13 .686 .471 -.171 .261 -.843 .517 C4. You like cooperative learning. 3.98 .690 .476 -.861 .261 3.08 .517 C5. You will adopt this type of learning to study at university. 3.92 .676 .457 .100 .261 -.772 .517 Me1. You have much guidance on studying interpreting. 3.66 .682 .466 -.368 .261 .160 .517 Me2. You are permitted to explore theories before practicing in class. 3.98 .756 .571 -.639 .261 .567 .517 Me3. You can apply what you have learnt to practicing interpreting skills. 3.75 .785 .617 -.738 .261 1.21 .517 Me4. You find the theories helpful for practicing interpreting. 3.79 .742 .550 -.534 .261 .370 .517 T1. Your present teacher of Interpreting 2 is knowledgeable in teaching interpreting. 4.15 .588 .345 -.397 .261 1.49 .517 T2. He is helpful and caring. 4.24 .570 .325 -.420 .261 1.81 .517 T3. He knows good ways to help you improve interpreting skills. 4.19 .627 .393 -.456 .261 .853 .517 G1. You find the current approach to teaching interpreting more effective than that in Interpreting 1. 4.31 .740 .548 -.742 .261 -.148 .517 G2. You like the current approach to interpreting. 4.18 .710 .504 -.473 .261 -.152 .517 More specifically, the items marked as M1 - M5 are concerned with the choice of materials for practice in class, and it is exciting to know that the means of these items are above the agreement level of 3.41. However, though students agree with all the statements, the statistics figure out that they are not completely satisfied with the source texts chosen by their peers. This is because they are grouped on the basis of convenience, not of interest; thus, each member follows a different interest and need, and they hardly agree to one and the same topic. In addition, because the Skewness and the Kurtosis are negative (except M4), the data spreads further to the left of the mean and the data distribution is quite flat accordingly. The items marked as L1-L5 center on the student subjects’ language proficiency in the practice and production stages. Except for the response to L3, which bears the mean below the agreement level (3.33), the remainder is with high levels of rating, showing that the student subjects are satisfied with their practice and believe that cooperation in learning can improve their language skills. Additionally, the Skewness (except L2) shows that the data spread to both sides of but close to the means. Overall, although the student subjects are not really critical of their peers’ interpreting, the statistics point out that cooperation is helpful for their learning. For the items marked as C1-C5 in Table 2, the means of the ratings are quite high, showing that the student subjects agree with all the claimed statements in the questionnaire. However, the Skewness shows that most of the data (except C5) spreads to the left side of the means. However, in C4, the Kurtosis peaks 3.08, showing that the data distribution is sharply high to the right of the means, while the rest fall quite flat. In short, the student subjects are satisfied with the cooperation to improve their confidence. This finding concurs with the less uncertainty of vocabulary choice and better use of voice and intonation mentioned in Section 3.1. The items coded as Me1-Me4 focus on the methods of teaching in class. The responses of this factor well reach the level of agreement. While the Skewness indicates that the data spreads more to the left of the means, the Kurtosis shows that the condensed data reaches the considerable height to the right of the mean, especially for Me3 whose Kurtosis tops at 1.21. In fact, the standard deviation and the variance of Me3 are higher than those of the other items, revealing that the students are a little diverse in applying the theory into real life. This is true because the skills of memory, visualization and not-taking need improving through the time. They cannot be formed in one day; the students find it hard to master them. The teacher is the last factor that needs analyzing; however, it is interesting to see that this factor is with the highest ratings, revealing that the students are satisfied with the teacher most. Because the means are quite high, the Skewness is negative and falls far to the left in all the items, and the Kurtosis indicates some sharp heights of the data distribution in T2 and T1 that hit 1.81 and 1.49, centering to the right of the means respectively. In general, the statistics show that the teacher is the most satisfying in the class room; thus, he is the most influential and inspiring factor of the five ones mentioned above. The last two items marked G1 and G2 in Table 2 help the student subjects confirm the use of the constructivist approach to learning interpreting, and the responses are quite positive, especially G1, which affirms that the current approach is more effective than the previous one in Interpreting 1. This, moreover, reveals that the approach should be applied on a much larger basis. To understand more about this, the author decides on doing the cross table statistics provided in Table 3 below. Table 3. Correlation between score and like of the constructivist approach You like the current approach to interpreting. Total 2 3 4 5 Your score of Interpreting 1 5 to below 7 1 7 18 15 41 7 to 8 0 5 23 13 41 above 8 0 0 2 1 3 Total 1 12 43 29 85 Table 3 shows that only one of the student subjects disagrees with the approach, and twelve others hold their neutral stance; meanwhile, the rest (making up about 85%) support and like it. Also seen in Table 3, the higher score the supporters get, the more they like the approach, indicating that better students prefer it. On the whole, the observation and the questionnaire help uncover some myth related to the newly applied approach to teaching interpreting, and the findings show that the empirical work is quite successful. The student subjects give the high rakings to show their complete agreement in the benefit of cooperation in learning interpreting (L4), group discussion in broadening knowledge (C1), the teacher’s help and care (T2) and the effectiveness of the newly applied approach to interpreting (G1). 5. Conclusion The students’ experiences in and perception of the application of constructivism and cooperative learning in Interpreting 2 have been described, analyzed and reported in the paper. The results of the six-week-long empirical courses have proven some initial success, and students show much interest in studying interpreting. The observation shows that the students are keen on learning interpreting when experiencing the new approach. The factor analysis of material choice, language proficiency, confidence, methods and the teacher get high rankings, asserting that the student subjects are satisfied with the new approach. The data gathered in the questionnaire, in addition, reveals that they like the approach, and they want it to be applied more. Therefore, it is highly expected that teaching and learning interpreting at HEIs should be based on this approach. Apart from the positive results mentioned above, there are some disadvantages that need addressing to get better success. Firstly, when grouped, the students should be advised to choose the peers on the basis of needs and interest. This will help them choose materials much more easily and appropriately. Secondly, although there are criteria for choosing the proper texts for practice, students still tend to pick the one which is less challenging or to simplify the text to make it much easier. Thirdly, each group often chooses one text, and the members only focus on practicing it. Fourthly, the new approach should be combined with technology because everyone is now working with information technology tools; thus, teaching them to master IT tools should be a must at tertiary level. Finally, students should take better advantage of cooperative learning as after-school assignments because they have more time at home, and they can group to improve their skills much better. References Alzahrani, I., & Woollard, J. (2013). The role of the constructivist learning theory and cooperative learning environment on wiki classroom, and the relationship between them. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference for E-learning and Distance Education (pp. 2- 9). Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Can, T. (2009). Learning and teaching language online: A constructivist approach. Novista Royal Research on Youth and Language, 3(1), 60-74. Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: The Free Press. Felder, R.M., & Brent, R. (2007). Cooperative learning. In Active learning: Models from the Analytical Sciences. ACS Symposium Series, vol. 970, (pp. 34-53). Washington DC: American Chemical Society. Kuhn, T. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd edition). Chicago: Chicago University Press. Law, W. (2009). Translation students' use of dictionaries: A Hong Kong case study for Chinese-English translation. PhD dissertation. Hong Kong: University of Durham. Newmark, P. (1988). A textbook of translation. The USA: Prentice Hall. Nguyễn Quang Nhật (2016). Giảng dạy biên phiên dịch trong bối cảnh hội nhập - Dạy học theo phương pháp tiếp cận năng lực. Teaching translation and interpretation at tertiary level (pp. 110-122). Ho Chi Minh: VNUHCM Publisher. Nguyễn Quốc Hùng (2012). Hướng dẫn biên phiên dịch Việt-Anh, Anh-Việt. Hồ Chí Minh: Nxb Tổng Hợp. Nguyễn Thị Kiều Thu (2016). Đánh giá bản dịch: tiêu chí chấm bài biên dịch trong các trường đại học. Teaching translation and interpretation at tertiary level (pp. 55-69). Ho Chi Minh: VNUHCM Publisher. Nguyễn Thị Như Ngọc, Nguyễn Thị Kiều Thu & Lê Thị Ngọc Anh (2016). Khảo sát thực trạng hoạt động đào tạo biên phiên dịch tiếng Anh tại một số trường đại học tại Việt Nam hiện nay. Teaching translation and interpretation at tertiary level (pp. 2-20). Ho Chi Minh City: VNUNCM Publisher. Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

File đính kèm:

constructivism_and_cooperative_learning_an_application_in_te.pdf

constructivism_and_cooperative_learning_an_application_in_te.pdf